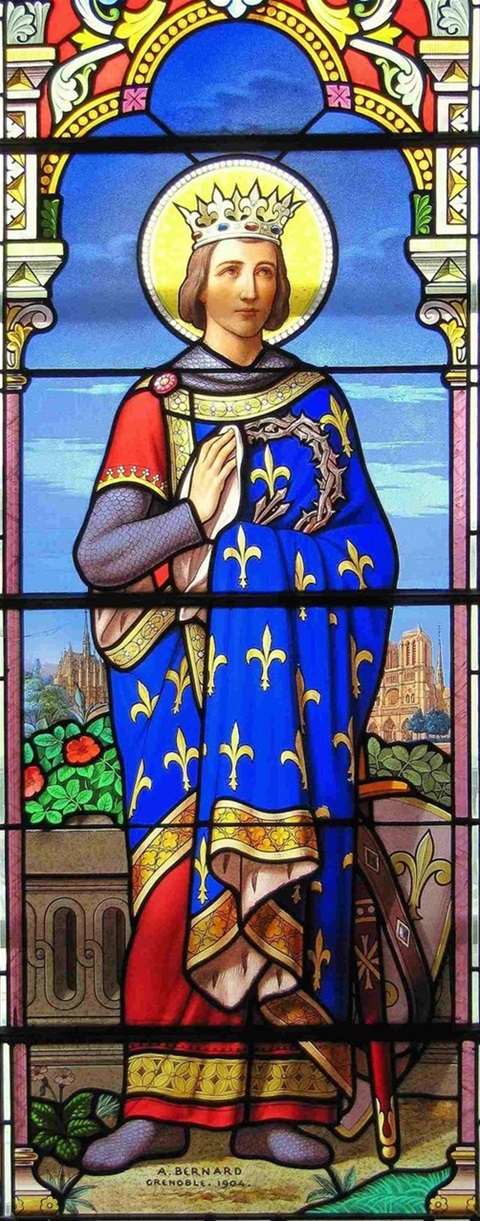

August 25, 2022: ST. LOUIS (IX), KING OF FRANCE

August 25, 2022: ST. LOUIS, KING, CONFESSOR

Rank: Simple.

“Thou hast chosen me to be king of thy people, and a judge of thy sons and daughters. And hast commanded me to build a temple on thy holy mount, and an

altar in the city of thy dwelling-place, a resemblance of thy holy tabernacle, which thou hast prepared from the beginning.”

(Wisdom, ix.

7, 8)

“He made a covenant before the Lord to walk after Him and keep His commandments; and cause them to be kept by all.”

(II Paralip, xxxiv. 31-33)

“Blessed is the man that feareth the Lord: he shall delight exceedingly in his commandments. His seed shall be mighty upon earth: the generation of the righteous shall be

blessed.”

(Ps, cxi. 1-2)

Prayer (Collect).

O God, who didst remove blessed Lewis thy Confessor from an earthly kingdom to the glory of an heavenly crown; grant, we beseech thee, in favour of his virtues, and by the help of his prayers, we may be received into the company of the King of Kings, Jesus Christ thy only Son. Who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God, world without end. Amen.

Click here, to read the detailed Letter given by St. Louis IX on his death-bed to his son, Philip III.

IT was his Christian faith that made Louis IX so great a prince. ‘You that are the judges of the earth, think of the Lord in goodness, and seek Him in simplicity of heart.’ (Wisdom, i. 1) Eternal Wisdom, in giving this precept to kings, rejoiced with divine foreknowledge among the lilies of France, where this great saint was to shine with so bright a lustre.

Subject and prince are bound to God by a common law, for all men have one entrance into life, and the like going out. (Wisdom, vii. 6) Far from being less responsible to the divine authority than his subjects, the prince is answerable for every one of them as well as for himself. The aim and object of creation is that God be glorified by the return of all creatures to their Author, in the manner and measure that He wills. Therefore, since God has called man to a participation in His own divine life, and has made the earth to be to him but a place of passage, mere natural justice and the present order of things are not sufficient for him. Kings must recognize that the object of their civil sovereignty, not being the last end of all things, is, like themselves, under the direction and absolute rule of that higher end, before which they are but as subjects. Hear therefore, ye kings, and understand: a greater punishment is ready for the more mighty. (Wisdom, vi. 2, 9) Thus did the divine goodness give merciful warnings under the ancient Covenant.

But not satisfied with giving repeated admonitions, Wisdom came down from her heavenly throne. Henceforth the world belongs to her by a twofold title. By the right of her divine origin, she held the principality in the brightness of the saints, before the rising of the day star; she now reigns by right of conquest over the redeemed world. Before her coming in the flesh, it was already from her that kings received their power, and that equity which directs its exercise. Jesus, the Son of Man, whose Blood paid the ransom of the world, is now, by the contract of the sacred nuptials which united Him to our nature, the only source of power and of all true justice. And now, once more, O ye kings, understand: says the psalmist; receive instruction, you that judge the earth. (Psalm, ii. 10)

‘It is Christ who speaks:’ says St. Augustine. ‘Now that I am king in the name of God My Father, be not sad, as though you were thereby deprived of some good you possessed; but rather acknowledging that it is good for you to be subject to Him who gives you security in the light, serve this Lord of all with fear, and rejoice unto Him.’

It is the Church that continues, in the name of our ascended Lord, to give to kings this security which comes from the light: the Church who, without trespassing upon the authority of princes, is nevertheless their superior as mother of nations, as judge of consciences, as the only guide of the human race journeying towards its last end. Let us listen to the sovereign Pontiff Leo XIII, speaking with the precision and power which characterize his infallible teaching: ‘As there are on earth two great societies: the one civil, whose immediate end is to procure the temporal and earthly well-being of the human race; the other religious, whose aim is to lead men to the eternal happiness for which they were created: so also God has divided the government of the world between two powers. Each of these is supreme in its kind; each is bounded by definite limits drawn in conformity with its nature and its peculiar end. Jesus Christ, the founder of the Church, willed that they should be distinct from one another, and that both should be free from trammels in the accomplishment of their respective missions; yet with this provision, that in those matters which appertain to the jurisdiction and judgment of both, though on different grounds, the power which is concerned with temporal interests, must depend, as is fitting, on that power which watches over eternal interests. Finally, both being subject to the eternal and to the natural Law, they must in such a manner mutually agree in what concerns the order and government of each, as to form a relationship comparable to the union of soul and body in man.’

In the sphere of eternal interests, to which no one may be indifferent, princes are bound to hold not only themselves but their people also in subjection to God and to His Church. For ‘since men united by the bonds of a common society depend on God no less than individuals, associations whether political or private cannot, without crime, behave as if God did not exist, nor put away religion as something foreign to them, nor dispense themselves from observing, in that religion, the rules according to which God has declared that He wills to be honoured. Consequently, the heads of the State are bound, as such, to keep holy the name of God, make it one of their principal duties to protect religion by the authority of the laws and not command or ordain anything contrary to its integrity.’

Let us now return to St. Augustine’s explanation of the text of the Psalm: ‘How do kings serve the Lord with fear, except by forbidding and punishing with a religious severity all acts contrary to the commands of the Lord? In his twofold character as man and as prince, the king must serve God: as man, he serves Him by the fidelity of his life; as king, by framing or maintaining laws which command good and forbid evil. He must act like Ezechias and Josias, destroying the temples of the false gods and the high places that had been constructed contrary to the command of the Lord; like the king of Ninive obliging his city to appease the Lord; like Darius giving up the idol to Daniel to be broken, and casting Daniel’s enemies to the lions; like Nabuchodonosor forbidding blasphemy throughout his kingdom by a terrible law. It is thus that kings serve the Lord as kings, viz: when they do in His service those things which only kings can do.’

In all this teaching we are not losing sight of to-day’s feast; for we may say of Louis IX as an epitome of his life: ‘He made a covenant before the Lord to walk after Him and keep His commandments; and cause them to be kept by all.’ (II Paralip, xxxiv. 31-33) God was his end, faith was his guide: herein lies the whole secret of his government as well as of his sanctity. As a Christian he was a servant of Christ, as a prince he was Christ’s lieutenant; the aspirations of the Christian and those of the prince did not divide his soul; this unity was his strength, as it is now his glory. He now reigns in heaven with Christ, who alone reigned in him and by him on earth. If then your delight be in thrones and sceptres, O ye kings of the people, love wisdom, that you may reign for ever. (Wisdom, vi. 22)

Louis was anointed king at Rheims on the first Sunday of Advent 1226; and he laid to heart for his whole life the words of that day’s Introit: ‘To Thee, O Lord, have I lifted up my soul: in Thee, O my God, I put my trust!’ He was only twelve years old; but our Lord had given him the surest safeguard of his youth, in the person of his mother (Blanche of Castille), that noble daughter of Spain, whose coming into France, says William de Nangis, was the arrival of all good things. The premature death of her husband Louis VIII left Blanche of Castille to cope with a most formidable conspiracy. The great vassals, whose power had been reduced during the preceding reigns, promised themselves that they would profit of the minority of the new prince, in order to regain the rights they had enjoyed under the ancient feudal system to the detriment of the unity of government. In order to remove this mother, who stood up single-handed between the weakness of the heir to the throne and their ambition, the barons, everywhere in revolt, joined hands with the Albigensian heretics; and made an alliance with the son of John Lackland, Henry III, who was endeavouring to recover the possessions in France lost by his father in punishment for the murder of prince Arthur. Strong in her son’s right and in the protection of Pope Gregory IX, Blanche held out; and she, whom the traitors to their country called the foreigner in order to palliate their crime, saved France by her prudence and her brave firmness. After nine years of regency, she handed over the nation to its king, more united and more powerful than ever since the days of Charlemagne.

We cannot here give the history of an entire reign; but, honour to whom honour is due: Louis, in order to become the glory of heaven and earth on this day, had but to walk in the footsteps of Blanche, the son had but to remember the precepts of his mother.

There was a graceful simplicity in our saint’s life, which enhanced its greatness and heroism. One would have said he did not experience the difficulty that others feel, though far removed from the throne, in fulfilling those words of our Lord: Unless you become as little children, you shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven. (St. Matth, xviii. 3) Yet who was greater than this humble king, making more account of his Baptism at Poissy than of his anointing at Rheims; saying his Hours, fasting, scourging himself like his friends the Friars Preachers and Minors; ever treating with respect those whom he regarded as God’s privileged ones, priests, religious, the suffering and the poor? The great men of our days may smile at him for being more grieved at losing his breviary than at being taken captive by the Saracens. But how have they behaved in the like extremity? Never was the enemy heard to say of any of them: ‘You are our captive, and one would say we were rather your prisoners.’ They did not check the fierce greed and bloodthirstiness of their gaolers, nor dictate terms of peace as proudly as if they had been the conquerors. The country, brought into peril by them, has not come out of the trial more glorious. It is peculiar to the admirable reign of St. Louis, that disasters made him not only a hero but a saint; and that France gained for centuries in the east, where her king had been captive, a greater renown than any victory could have won for her.

The humility of holy kings is not forgetfulness of the great office they fulfil in God’s name; their abnegation could not consist in giving up rights which are also duties, any more than charity could cast out justice, or love of peace could oppose the virtues of the warrior. St. Louis, without an army, felt himself superior as a Christian to the victorious infidel, and treated him accordingly; moreover the west discovered very early, and more and more as his sanctity increased with his years, that this king, who spent his nights in prayer, and his days in serving the poor, was not the man to yield to anyone the prerogatives of the crown. ‘There is but one king in France,’ said the judge of Vincennes rescinding a sentence of Charles of Anjou; and the barons at the castle of Bellême, and the English at Taillebourg, were already aware of it; so was Frederick II who, threatening to crush the Church and seeking aid from the French, received this answer: ‘The kingdom of France is not so weak as to suffer itself to be driven by your spurs.’

Louis’s death was like his life, simple and great. God called him to Himself in the midst of sorrowful and critical circumstances, far from his own country, in that African land where he had before suffered so much; these trials were sanctifying thorns, reminding the prince of his most cherished jewel, the sacred crown of thorns which he had added to the treasures of France. Moved by the hope of converting the king of Tunis to the Christian faith, it was rather as an apostle than a soldier that he had landed on that shore where his last struggle awaited him. ‘I challenge you in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of His lieutenant Louis king of France;’ such was the sublime provocation hurled against the infidel city, and it was worthy of the close of such a life. Six centuries later, Tunis was to see the sons of those same Franks unwittingly following up the challenge of the saintly king, at the invitation of all the holy ones resting in the now Christian land of ancient Carthage.

The Christian army, victorious in every battle, was decimated by a terrible plague. Surrounded by the dead and dying, and himself attacked with the contagion, Louis called to him his eldest son, who was to succeed him as Philip III, and gave him his last instructions: ‘Dear son, the first thing I admonish thee is that thou set thy heart to love God, for without that nothing else is of any worth. Beware of doing what displeases God, that is to say mortal sin; yea rather oughtest thou to suffer all manner of torments. If God send thee adversity, receive it in patience, and give thanks for it to our Lord, and think that thou hast done Him ill service. If He give thee prosperity, thank Him humbly for the same and be not the worse, either by pride or in any other manner, for that very thing that ought to make thee better; for we must not use God’s gifts against Himself. Have a kind and pitiful heart towards the poor and the unfortunate, and comfort and assist them as much as thou canst. Keep up the good customs of thy kingdom, and put down all bad ones. Love all that is good and hate all that is evil of any sort. Suffer no ill word about God or our Lady or the saints to be spoken in thy presence, that thou dost not straightway punish. In the administering of justice be loyal to thy subjects, without turning aside to the right hand or to the left; but help the right, and take the part of the poor until the whole truth be cleared up. Honour and love all ecclesiastical persons, and take care that they be not deprived of the gifts and alms that thy predecessors may have given them. Dear son, I admonish thee that thou be ever devoted to the Church of Rome, and to the sovereign Bishop our father, that is the Pope, and that thou bear him reverence and honour as thou oughtest to do to thy spiritual father. Exert thyself that every vile sin be abolished from thy land; especially to the best of thy power put down all wicked oaths and heresy. Fair son, I give thee all the blessings that a good father can give to a son; may the blessed Trinity and all the saints guard thee and protect thee from all evils; may God give thee grace to do His will always, and may He be honoured by thee, and may thou and I after this mortal life be together in His company and praise Him without end.’

‘When the good king,’ continues Joinville, ‘had instructed his son my lord Philip, his illness began to increase greatly; he asked for the Sacraments of holy Church, and received them in a sound mind and right understanding, as was quite evident; for when they were anointing him and saying the seven Psalms, he took his own part in reciting. I have heard my lord the Count d’Alençon his son relate, that when he drew nigh to death, he called the saints to aid and succour him, and in particular my lord St. James, saying his prayer which begins: Esto Domine; that is to say: O God, be the sanctifier and guardian of thy people. Then he called to his aid my lord St. Denis of France, saying his prayer, which is as much as to say: Sire God, grant that we may despise the prosperity of this world, and may fear no adversity! And I heard from my lord d’Alencon (whom God absolve), that his father next invoked Madame St. Genevieve. After this the holy king had himself laid on a bed strewn with ashes, and placing his hands upon his breast and looking towards heaven, he gave up his soul to his Creator, at the same hour wherein the Son of God died on the cross for the salvation of the world.’

Let us read the short notice consecrated by the Church to her valiant eldest son.

Louis IX, king of France, having lost his father when he was only twelve years old, was educated in a most holy manner by his mother Blanche. When he had reigned for twenty years he fell ill and it was then he conceived the idea of regaining possession of Jerusalem. On his recovery therefore he received the great standard from the bishop of Paris and crossed the sea with a large army. In a first engagement he repulsed the Saracens; but a great number of his men being struck down by pestilence, he was conquered and made prisoner.

A treaty was then made with the Saracens, and the king and his army were set at liberty. Louis spent five years in the east. He delivered many Christian captives, converted many of the infidels to the faith of Christ, and also rebuilt several Christian towns out of his own resources. Meanwhile his mother died, and on this account he was obliged to return home, where he devoted himself entirely to good works.

He built many monasteries and hospitals for the poor; he assisted those in need and frequently visited the sick, supplying all their necessities at his own expense and even serving them with his own hands. He dressed in a simple manner and subdued his body by continual fasting and wearing a hair-cloth. He crossed over to Africa a second time to fight with the Saracens, and had pitched his camp in sight of them when he was struck down by a pestilence and died while saying this prayer: ‘I will come into thy house; I will worship towards thy holy temple and I will confess to thy name.’ His body was afterwards translated to Paris and is honourably preserved in the celebrated church of St. Denis; but the head is in the Sainte-Chapelle. He was celebrated for miracles, and Pope Boniface VIII enrolled his name among the saints.

Taken from: The Liturgical Year - Time after Pentecost, Vol. V, Edition 1910; and

The Divine Office for the use of the Laity, Volume II, 1806.

St. Louis, pray for us.