February 27, 2021: ST. GABRIEL OF OUR LADY OF SORROWS

February 27, 2021: ST. GABRIEL OF OUR LADY OF SORROWS

Rank: Double.

“the eye of God hath looked upon him for good, and hath lifted him up from his low estate, and hath exalted his head: and many have

wondered at him, and have glorified God.”

(Ecclus, xi. 13)

“Being made perfect in a short space, he fulfilled a long time; for his soul pleased God”

(Wis, iv. 13)

Prayer (Collect).

O God, You taught blessed Gabriel to dwell continually upon the sorrows of Your most sweet Mother, and have raised him to the glory of holiness and miracles; grant us through his intercession and example, so to share in the mourning of Your Mother, that we may be saved by her maternal protection. Who liveth and reigneth, world without end. Amen.

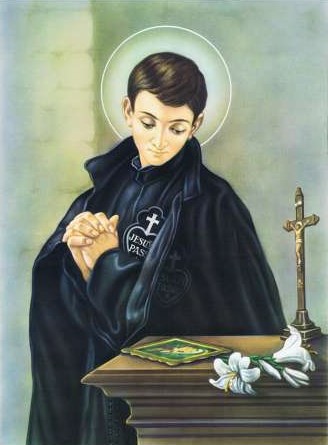

St. Gabriel was born at Assisi in 1838. He was guided by our Lady into the Passionist Institute and became a veritable Apostle of her Sorrows. At twenty-four years of age, he died of consumption, having already attained to a heroic degree of sanctity by a life of self-denial and great devotion to our Lord’s Passion. He is the patron of the youth and especially of young religious.

St. Gabriel, of Our Lady of Sorrows, Passionist

A Youthful Hero of Sanctity

(by Rev. Fr. Reginald Lummer, C.P., Edition 1920, Imprimatur)

A Passion Flower

The mountains of Italy are covered with tall pines, great beeches, and spreading chestnuts. Vines and olives are planted in the valleys and on the hills. On the roadside and in the gardens roses, camellias, and lilies grow in profusion. So, too, in the gardens of Paradise there are saints who, by loftiness of intellect, have raised themselves, like the cedars of Lebanon, high above their fellowmen. These are the Augustines and the Chrysostoms. Others, like the beech and the chest nut, have spread their loving arms to shelter and protect great families of religious men and women. These are the Benedicts and Dominics. Saintly penitents and confessors are the vines and olives, made fruitful by the plough of probation and the pruning knife of penance. Virgins are the lilies, and martyrs are the red roses and crimson camellias of God’s garden. But there are daisies in the field as well as roses in the hedge; there are passion flowers beside the wall as well as pines on the mountain.

At the foot of the Apennines, under the shadow of the Gran Sasso of Italy, out of the beaten track of travelers, and hidden from the eyes of men within the walls of a monastery grew a modest passion flower, sweet and beautiful. It was hidden from the world, but not from God. He looked down upon it; His grace bedewed it; His love shone upon it. And then He stooped gently to lift and transplant it to the garden of His saints. This modest passion-flower, that now grows among the more brilliant flowers of Paradise, and under the shade of its great trees, is Saint Gabriel, Passionist, known, before he entered religion, as Francis Possenti.

Childhood

Francis was the son of Signor Possenti, a lawyer of great talent, who was appointed Governor of Umbria, in Romagna, Italy, when barely twenty years old, and who, before retiring from public service, became Grand Assessor of Spoleto. Francis’ mother belonged to one of the best families of Civitanova, in the Marches. Both father and mother were distinguished, not only by birth and position, but also for their piety and Christian virtues.

Francis was the eleventh of thirteen children. He was born at Assisi on the first day of March, 1838. His father had not yet been made Grand Assessor of Spoleto. The child was baptized on the day of his birth, at the same font where, over six hundred years before, another Francis, the great patriarch of the city and glorious saint, was baptized.

Before he was quite four years old Francis lost his pious and beloved mother. Four of her children had died before her. Signor Possenti, though stricken with grief at the untimely death of his tender and affectionate wife, neglected neither the important duties of a governor nor the responsible obligations of a father. He entrusted the management of his household, as well as the care of his nine children, to a responsible and experienced lady named Pacifica.

The education of Francis was begun by Pacifica, a tutor, and his pious father. On the whole, he was a good boy, but in these early years he manifested very few signs of the sanctity for which he was to be so distinguished in after years. He was, if anything, the gayest and liveliest of the family. A proneness to anger, levity, and disobedience was his principal fault. When corrected by his father, his unruly temper would reveal itself by his inflamed face, and by the abrupt manner in which he would leave the company. But his anger would cool as quickly as it had heated, and in a few moments he would return in tears to beg pardon of his father. His tutor, Philip Fabi, a young cleric of piety and learning, had by no means an easy task. In his childhood Francis was changeable and fickle. At one time he would be full of fervor at his studies and religious duties, and at others careless and indifferent. His tender sympathy, however, and his loving kindness made him a great favorite with his brothers and sisters at home, and with his playmates elsewhere. Hardly had he come to the use of reason before he began to show a marked thoughtfulness and friendship for the poor. He would deny himself to give to them. The charitable Pacifica could not always satisfy the demands he made upon her for those in need. To her objections Francis would answer: “Why! . . . Father wants us to be charitable; we ought not to despise the poor, for we don’t know what we may one day be ourselves.”

Youth and School Life

The education of Francis, begun by his father, Philip Fabi, and Pacifica, at home, was continued by the Brothers of the Christian Schools, and finished by the Jesuit Fathers at Spoleto. Signor Possenti assumed the office of Grand Assessor there in 1842, about the time of his wife’s death.

At school Francis quickly made himself a favorite with both companions and teachers. He was brave and outspoken. To the suffering he was a warm-hearted sympathizer; to the weak and persecuted, a fearless champion; to companions, a stanch friend; and to masters, a willing and talented pupil. In those days few prizes were given at school, but Francis was the winner of more than one. His professor in mental philosophy said that he was one of his aptest scholars. He was selected as public reader, both for the sodality at the college and for the catechism class held in its church on public festivals. At the public exhibitions of school and college the most difficult parts generally fell to the lot of our hero.

Francis finished his public school course at the Jesuit College at the age of eighteen years. He entered society before he left college. The fickleness of mind that had manifested itself in his childhood appeared again from time to time in his early manhood. It was revealed by his manner of dressing. For a time he would be so fastidious in dress as to become almost foppish, and then again he would take little heed of style or fashion. He indulged rather freely in novel-reading and theatre-going–dangerous pastimes for one of his years. Francis afterwards referred to the risks to which he had exposed both mind and morals by indulging these tendencies. After entering the monastery he wrote to a friend: “Dear Philip, if you truly love your soul, shun evil companions, shun the theatre. I know by experience how very difficult it is, while entering such places in the state of grace, to come away without either having lost it, or at least exposed it to great danger. Shun pleasure parties, and shun evil books. I assure you that, if I had remained in the world, it seems certain to me that I would not have saved my soul. Tell me, could anyone have indulged in more amusements than I? Well, and what is the result? Nothing but bitterness and fear.” Yet neither Francis’ brothers and sisters, nor his companions at school, ever saw anything very reprehensible in his conduct. He was regular in his religious duties, never neglected his morning and evening prayers, and assisted daily at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

Signer Possenti’s talents and honorable position gave him a high social standing, and his son could move in the best society of Spoleto. Francis found the doors of all the leaders of society there open to him. He kept them open, and won a hearty welcome for himself wherever he went by his accomplishments and winning ways. He was fond of music, and could always contribute a fair share to the evening’s entertainment. He was fond of the dance. Handsome in person and graceful in movement, he was always an acceptable partner. He was fond of the theatre, and could always take a leading part in private performances. He was successful at college; he was successful in society. Everyone said that he would be successful in whatever he undertook, and that a brilliant career lay before him in the world.

The day that closed his college course was a day of triumph for Francis. Handsome appearance, graceful address, expressive gesture, command of language, and good voice had gained for him first place among the young men of the Jesuit College. He was chosen to deliver the opening discourse at the commencement exercises. A brilliant audience of learned and aristocratic men and women were assembled in the large hall. A friend of the young orator for the occasion has left us a minute description of him as he stood on the stage. “His clothes,” he says, “were unusually elegant; a matchless and richly-folded shirt-front adorned with jewels; bright buttons on his cuffs; a silk cravat around his neck; his hair studiously parted. Add to these his white kid gloves and patent-leather shoes, and we have a pen picture of young Francis Possenti as he stood, smiling and serene, facing his many friends and the distinguished audience about to be pleased spectators of his triumph.” The audience was delighted with his address. They loudly applauded and cheered when he was presented with a gold medal for excellence in all his studies.

Those who gazed upon and cheered the handsome youth, all flushed with success, little suspected that, in bowing them his acknowledgments, he was taking leave of them and worldly society. Gifted with much talent, assured of worldly success, and favored by society, he was going to renounce the brilliant career that lay before him in the world to become a priest. None of the audience, except his father, suspected that he was about to turn his back on the pomps and pleasures of the world to give himself entirely to the service of God in a monastery. None of them knew that he was going to cast off all that finery of dress to clothe himself in the poor habit of a Passionist. None of those who so joyfully cheered and applauded knew that the day of his triumph was the eve of his departure from them. When Francis parted with his friends that night, and said good-bye to them, they thought that he was only going for a holiday. The next day he left home and set out for the Passionist Novitiate at Morrovalle, in the province of Macerata.

Vocation

The religious vocation of Francis, not known to his friends until after his departure, had been secretly hidden in his breast for some years. Though so gay in manner, and seemingly so thoughtless, he had been thinking seriously of the future. A secret impulse urged him to use his talents and spend his energy in the service of God and of His Church. “How many times,” writes his friend, Bonaccia, “do I remember seeing him during his thanksgiving after Communion, his head bowed in deepest reverence, his hands clasped, his eyes moist with silent tears, as if he were pondering over some great thought, and maturing with God some great design?” Twice Francis had been seriously ill, and seemed in danger of death. On both of these occasions he had promised God in his heart that, if he were spared, he would enter a Religious Order. The promises were evidently accepted, for each time they were made the ailing youth quickly recovered. After the second of these illnesses and extraordinary cures, he went to the Father Provincial of the Jesuits, and asked to be received into the Society. His request was granted, but he dillydallied with his vocation. He did not refuse to fulfil his promise to God, but again and again deferred its fulfillment. Whilst thus hesitating to answer his vocation, and delaying to make use of the permission given him by the Father Provincial of the Jesuits, Francis began to think of becoming a Passionist. In his doubt and difficulty he asked the advice of Father Peter Tedeschini, S.J. This holy priest told him to wait and pray for further guidance.

How wonderfully patient God is with us! He had twice cured Francis of his sickness, and now He gave the reluctant youth a more decisive call to duty. In the year 1856 the terrible ravages of cholera had been suddenly stopped at Spoleto through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin. In public gratitude for this miraculous favor, her statue was carried in procession through the streets of the city. Francis watched the procession rather through curiosity than devotion. As the statue was borne past, he raised his eyes, and, through the eyes of the statue, Mary cast upon him a glance that pierced his inmost heart as with a dart of fire. At the same time, deep within his soul, he heard the words: “Why! . . . thou art not made for the world! What art thou doing in the world? Hasten, become a religious!” The procession passed on, but Francis remained kneeling in prayer at the roadside. No one but he had seen or heard anything extraordinary. He cried out with gratitude for the signal favor bestowed upon him. He thanked the Blessed Virgin again and again for her loving warning. From that moment he was a changed boy. He no longer thought of anything but of fulfilling his vocation. He determined to become a Passionist. That resolution was made less than a month before the brilliant closing of his college career. Within that time he revealed his determination, first to his spiritual director, and then to his father. He answered all objections against his choosing so hard a life, and completed arrangements with the Father Provincial of the Passionists for his entrance into the novitiate.

The news of his son’s determination was a double grief to Signer Possenti. It grieved him to lose so beloved and talented a son, and it grieved him that he should choose so rigorous a life. He was an aged man now, and few of his family remained at home. His eldest son, Aloysius, had joined the Domincans. Another son, Henry, had begun his studies for the priesthood. He had lost two daughters since the death of his wife one had died, the other had married and gone to a distant province. And now his beloved Francis the son that gave promise of bringing him so much honor the son who might have been the light and comfort of his old age was going to leave him. The aged father and his relations tried to persuade Francis to change his mind. They told him that the life of a Passionist would be too severe for him; that the plain food, coarse habit, and strict discipline would not suit one of such delicate tastes and refinement as he was. They reminded him of the honor that the world offered to one of his position and ability. They asked him, if he would not alter his intention of becoming a priest, to choose an easier rule than that of the Passionists, or to become a secular priest and stay nearer home. But Francis was firm. No worldly consideration could move him, no family tie could hold him. The desire to serve God and sanctify himself overruled every other desire. He dearly loved his father and his relations, but he loved God above all. As soon as Signor Possenti was convinced that his son was called by God, he at once ceased to oppose his wish. Father and son embraced each other and wept at parting. The man of years and honor bowed his head it seemed as if the sunshine were passing out of his life there was a void in his heart, tears fell from his eyes; but he made no complaint. There was no rebellion; his pious prayer was: “Thy will, O God, not mine, be done.”

Religious Life

Francis entered the Passionist Novitiate at Morrovalle in September, 1856. After living there in his secular dress for a short time, and making a retreat for ten days, he was clothed with the religious habit, and received the name of Gabriel, with the title of the Seven Dolors. We shall, therefore, no longer call him Francis, but Gabriel. This change of name is made in signification of authority over the person whose name is changed, and of the putting off of the old man and the putting on of the new, according to the advices of St. Paul.

As the soul of a traveler, dusty, wearied, and thirsty after crossing the hot and sandy plains, is delighted with the greenness and refreshed by the shade of an oasis, so the soul of Gabriel was delighted and refreshed with the peace and solitude of the monastery. No soldier was ever more truly proud of his uniform than Gabriel was of the habit that distinguished him as a soldier of Christ Crucified. Here is the letter that he wrote to his father on the day that he was first clothed as a Passionist:

“MORROVALLE, September 21, 1856.

“MY DEAR FATHER: The day has come at last. The Almighty had been calling me for a long time, whilst I ungratefully turned a deaf ear to His voice by enjoying the world and displeasing Him; but His infinite mercy

sweetly disposed all things, and today, the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, our Mother and Protectress, I was clothed in the holy habit, taking the name of Confrater Gabriel, of the Seven Dolors.

“Up to the present, my dear father, I have not experienced anything but pleasure, whether as regards this religious congregation or my vocation to it. Oh! rest assured that whosoever is called to the religious state receives a grace that he will never be able fully to comprehend.

“My excellent Father-Master and Vice-Master send their kind regards together with my own. My greetings to the Jesuits and Oratorians, as well as to all inquiring friends.

“Begging your blessing, dearest father,

I remain, your affectionate son,

CONFRATER GABRIEL,

Of the Dolors of Mary, Passionist.”

Twelve months must be spent by the Passionist novice in the novitiate before he can take the vows that make him a religious of the Congregation. These twelve months are a time of trial and probation. The novice living the life of a Passionist is given every opportunity to try it well before solemnly promising to continue it for the rest of his days. His superiors put his vocation to the test, and watch carefully to see if he is worthy to be admitted a member of the Congregation.

Gabriel loved the religious life from the moment he entered upon it. He fulfilled the rules of the Congregation with the greatest fervor and exactness, and was professed on the twenty-second of September, 1857. Besides the usual religious vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, a Passionist makes a particular vow to spread devotion to the passion of our Lord; hence, he is called a Passionist. The Sunday after his profession Gabriel wrote to his father as follows:

“Through the grace of God and the protection of Our Lady of Sorrows, and to my unspeakable joy, my desires have been fulfilled, and I have made my holy profession. Such a grace can never be valued adequately, and therefore, as I have been favored by Almighty God with such a privilege, I feel bound by an ever-increasing obligation to correspond thereto. I leave it, therefore, to your own judgment whether or no I stand in need of the prayers of yourself and others.”

When the year’s novitiate is ended those young men who are destined for the priesthood are formed into classes, and placed under the charge of a spiritual director and a professor. These students seldom remain in the retreat where the novitiate is, but are distributed among the other retreats of the province. Some time is spent in the study of classics, two years in philosophy, four years in theology, and then a course of sacred eloquence is gone through, before the young priests begin the public life of their sacred ministry.

After his profession Confrater Gabriel remained five months in the retreat at Morrovalle. Then, under the spiritual direction of Father Norbert, who had been his Vice-Master in the novitiate, he went with other students to Pieventorina in the Marches. Here he remained about eighteen months, before Father Norbert took his class to the retreat at Isola, in the province of Abruzzo, where Gabriel, after a residence of about three years, died.

There is nothing sensational to tell about the religious life of Gabriel. Passionist novices and students go through the same routine day after day, and week after week. After a rest of between four and five hours, they rise from bed a little after midnight to chant matins and lauds in the chapel, and spend some time in prayer. An hour and a half is spent in this way, and then the religious go to bed again for two or three hours. Between five and six o’clock they rise the second time, and go again to chapel. An hour and a half is spent there in chanting prime and tierce, in hearing Mass, and in mental prayer. The breakfast consists of a cup of coffee and a little bread. Three hours are given to study, quarter of an hour to spiritual reading, and half an hour to solitary walk, or work in the garden. Towards noon all the religious assemble for the third time in choir to chant sext and none. After dinner three-quarters of an hour are spent in recreation before the religious retire to their cells for an hour. At the sound of the bell they go the fourth time to chapel to chant vespers. The afternoon is spent, like the morning, in study, work, and solitary walk. In the evening all go to chapel for the fifth time to chant compline, which ends the divine office of the day. An hour is then passed in mental prayer, a light supper is taken, and, after another recreation of three-quarters of an hour, the religious say the Rosary and night prayers together before going to bed. The life of a Passionist at home is a continual round of prayer and study, with short intervals for manual work, solitary walk, and recreation. Except during the time of recreation, silence must be kept throughout the whole day. Students are not allowed to speak to anyone, even of their own number, without their director’s permission. They fast and abstain from meat three times a week, and during the whole of Lent and Advent. Their bed and pillow are of straw. Twice a week they are allowed to go beyond the enclosure of the retreat for a walk, under the guidance of their director. In Italy, once a religious lays aside the dress of a secular, he never puts it on again, but always wears the religious garb wherever he goes.

To one of the world that seems a most monotonous life. To one called to it by God it is the happiest life on earth. This was the life that Gabriel led for nearly six years. There was only one miraculous occurrence in his secular life, the warning given him by the Blessed Virgin through her image at Spoleto. There was nothing miraculous in his religious life. It was remarkable, not for great or extraordinary deeds, but for a complete change of life, a wonderful correspondence with God’s grace, and a marvelous exactness in every detail of his duties. In a letter to his brother, describing his daily duties, he says: “With joy, swiftness, and goodwill each day comes to an end. Oh, how pleasant it is to lay one’s self down to rest with the consciousness of having served God (however unworthily) during the whole day!”

A friend called one day on Michelangelo, who was finishing a statue. Some time afterwards he called again, and found the great sculptor still at the same work. His friend, looking at the statue, exclaimed: “You have been idle since I saw you last.” “By no means,” replied the sculptor; “I have retouched this part, and polished that; I have softened this feature, and brought out this muscle; I have given more expression to this lip, and more energy to this limb.” “Well, well,” said the friend, “but all these things are trifles.” “It may be so,” replied Michelangelo, “but remember that trifles make perfection, and that perfection is no trifle.”

Had the worldly-wise watched Gabriel at his work they would have regarded it with even less favor than Michelangelo’s friend regarded his. Had they seen Gabriel spending an hour morning and evening on his knees in silent prayer; had they seen him serving Mass with the simplicity of a child and the devotion of a saint; had they seen him from time to time making short visits to the Blessed Sacrament; had they seen him day after day doing the same things, studying at his desk, walking alone in the garden, never speaking or writing to anyone without his director’s permission, serving at the table in the refectory, washing the dishes in the kitchen, sweeping the corridor, scrubbing his cell, weeding the garden, and carrying his floral offerings to the statue of his beloved Virgin-Mother–had the worldly-wise seen this constantly and daily repeated, they would have said that it was all useless waste of time and energy, that Gabriel was burying his talents, and spoiling his life. But Gabriel was at a great work, the masterpiece of his life. He was at the greatest work that is given man to do the work of perfection. Trifles make perfection, and perfection is no trifle. By the menial work he did Gabriel was chipping off the rough edges of pride, and bringing out the lovely form of humility; by his simple life and coarse habit he was rubbing away the superfluities of vanity, and revealing the grace of modesty; by his poverty, chastity, and obedience he was toning down the rough defects of the man of nature, and producing a spiritual man of grace to the likeness of his Divine Model, Christ; by his frequent prayer and meditation, raising his mind from earth to heaven, he was bringing down and infusing a supernatural life into the work of his hands, and making it breathe and throb with the warmth of divine love.

The religious life of Gabriel was made up of trifles, and Gabriel was aware that they were trifles. But he was striving for perfection, and knew that trifles make perfection. His aim was perfection; his model was Christ Crucified; his patroness was the Mother of Sorrows; his guide was St. Paul of the Cross; his motive was the love of God. He gained his end, not by vainly longing to do great things that might never be given him to do, not by waiting for opportunities that might never occur, but by doing with all his might whatsoever his hand found to do. He wished to prolong his fasts, but his director told him to be satisfied with those imposed by the rules of the Congregation. He desired to practise great austerities, but was forbidden to attempt them. The rules of the Congregation were to him the expression of God’s will, and he fulfilled them to the letter as well as in the spirit. The sound of the observance bell was to him the voice of God calling him to his duty, and he hastened immediately to answer it. In the person of his superior he saw the person of Christ, and he humbly complied with his slightest wish. He ennobled the simplest act by the purity of his intention. What was trifling he made great by using it for an end. His constant occupation was the cultivation of the interior life by always subduing the defects of nature, by always corresponding with God’s grace, by always remembering God’s presence, and by always communing with Him in prayer. Charity is the bond of perfection, and Gabriel’s soul was aflame with charity.

No one can judge us so well as our companions. One of Gabriel’s most intimate companions in religion said: “I was never able to notice in him any willful defect or imperfection.” Father Norbert, his vice-master and spiritual director said: “Such was his hunger and thirst for all virtues, such the assiduity with which he labored for their acquisition, that he never lost an opportunity of practising them.” It was this longing desire for virtue, this continual reaching up to God that consumed Gabriel.

Flower of Passion

“Unless the grain of wheat falling unto the ground die, itself remaineth alone. But if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.” In the garden within the monastery walls at Isola stands a large crucifix. A seed fell to the ground before it. A plant sprang up, and twined itself around the cross until it reached the feet of the figure nailed upon it. It then bent outward, as if to behold what was above. A bud formed, swelled, burst into bloom, and gazed in loving awe upon the figure of Christ Crucified. Lo! it was a true flower of the Passion! Its heart was pierced and stamped with the signs of Him Who hung upon the cross. The seed that fell at the foot of the crucifix was Francis Possenti. The plant that grew therefrom and flowered was Gabriel of the Seven Dolors, Passionist.

When Gabriel was clothed he received the habit of a Passionist. When he was professed, besides making the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, he vowed to spread devotion to the Passion of Christ, and the sign of the Passion was attached to his breast. But the mere putting on of a black habit does not make a true Passionist; the wearing of a sign upon the breast does not make a true follower of Christ Crucified. Gabriel faithfully fulfilled his vows. He made the interior correspond to the exterior. The heart-shaped sign of the Passion without was no false badge of the heart within. The sufferings and death of Christ were subjects of daily meditation with Gabriel. The crucifix was always before his eyes, sometimes on the table before him at study, sometimes beside his book, often in his affectionate hands, and again and again pressed to his loving lips. It strengthened him in his trials; it comforted him in his tribulations; it inspired him in his meditations; it urged him to deeds of mortification and penance; it moved him to sorrow; it inflamed him with love. “May the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ be ever in our hearts!” is the meaning of the sign and motto upon a Passionist’s breast. The Passion of Christ was truly in the heart of Gabriel. It was heard in his words; it was seen in his actions; it was echoed in his life. He left the world, because Christ was not of the world. He was poor, because Christ was poor. He was chaste, because Christ was chaste. He was obedient, because Christ was obedient. He suffered, because Christ suffered.

Words fly, but example remains. Gabriel never preached from pulpit or platform. He never gave a mission to the people; yet very few have fulfilled their vow so well as he; very few have done so much to spread devotion to the Passion of Christ as he has done by the example of his life. He is preaching a sermon on the Passion that will never cease, a sermon that is heard at the ends of the earth.

Child of Mary

It was through Mary that Christ came into the world, and it is through Mary that the greatest saints have left the world and reached Christ. Mary, through her image at Spoleto, had warned Gabriel to leave the world and fulfil his vocation. One of Mary’s titles the title of the Seven Dolors was added to the name of Gabriel.

Gabriel’s soul was a furnace of love for Christ Crucified. He could not love the Son without loving the Mother. He could not gaze upon the crucified Son without beholding the Mother at the foot of the cross. He could not meditate upon the sufferings of Christ without thinking of the sorrows of Mary. No one loved Christ as Mary, His Mother, loved Him. Gabriel tried to reach the heart of Jesus through the heart of Mary. No one fathomed the depth of Christ’s sufferings as did his grief-stricken Mother. Gabriel tried to search those depths through her sympathetic eyes.

The Rule of St. Paul of the Cross advises all Passionists to “entertain a pious and ardent devotion towards the Immaculate Virgin Mother of God; let them strive to imitate her sublime virtues and merit her seasonable protection.” So well did Gabriel attend to this advice that Cardinal Parocchi, in his supplicatory letter to Pope Leo XIII says: “Mary was the very soul of Gabriel’s life, the source and model of the sanctity to which he attained; so that it may be truly said that in his devotion to the great Mother of God he has scarcely been equalled by any even of the greatest saints.”

This wonderful love and devotion to his heavenly Queen and Mother manifested themselves by a thousand different acts. He begged, but was refused, permission to burn the name of Mary upon his breast, or cut it into his flesh. It was his constant pleasure to attend to the garden, that flowers might be cultivated to adorn her statue. He called to her in times of danger and temptation; he sang to her in times of joy and victory. Her name was ever on his lips. He was all interest and eagerness when she was the subject of conversation. She was often the subject of his long and fervent meditations. Sometimes, forgetting the presence of his companions, he would murmur in an undertone: “Maria mia!” and his face would light up with joy.

He did not rest until, by repeated requests, he obtained permission from his director to bind himself by vow to be Mary’s champion for life. Her image, as well as that of her Divine Son, was on the picture that he kissed in his dying moments, and pressed to his heart. Mary and Jesus, Jesus and Mary, were in his heart, and on his lips, until his soul took flight and left the body.

Death

Gabriel, although never very robust, enjoyed very good health for the first four years of his religious life. He then began to manifest symptoms of consumption. As soon as his director noticed these signs of weakness, he forbade his rising for the midnight office and prayer, and dispensed him from the fasts of rule and all its penitential severities. These dispensations were displeasing to Gabriel, and nothing but the virtue of obedience would have induced him to accept them. Notwithstanding these precautions, and the attendance of a doctor, the deadly disease made rapid progress, and reduced its victim to a pitiable state of weakness. For months he suffered on a bed of pain, and was subject to violent hemorrhages. He bore all patiently, and without murmur or complaint. So cheerful was he that his fellow-students thought it a privilege to be allowed to watch at his bedside. When told that his end was near, he first manifested a little surprise, and then gladly resigned himself to the will of God. In his dying moments, after receiving absolution from his Father Director, he asked for an old picture of his, much worn by frequent use. It was a picture of the Crucifixion, with the Blessed Virgin standing at the foot of the cross. He devoutly kissed it, placed it on his breast, folded his hands across it, and began to speak in prayer. With indescribable love he began to say aloud: “Oh, my Mother make haste, make haste!” Commending his soul to God, he repeated the familiar ejaculation: “Jesus, Mary, Joseph, I offer you my heart and soul. Jesus, Mary, Joseph, assist me in my last agony. Jesus, Mary, Joseph, may I breathe forth my soul with you in peace.” His director, his fellow-students, and many of the community were watching and praying in his cell beside him. So devoutly did he raise his eyes to heaven, so sweetly did he pronounce the holy names of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, so tenderly did he call upon Mary to make haste, so lovingly did he supplicate his Divine Savior, that all were filled with awe and moved to tears. Suddenly he turned his eyes to the left and above him. He gazed upon some heavenly vision. His eyes beamed with transports of joy, long, loving sighs came from his heart; and then, with a sweet smile in his lips, and without the least movement of his body, he ceased to breathe. The Reaper had stooped and gathered the little passion flower.

Gabriel was not yet a priest when he died, in the twenty-fourth year of his age, and in the sixth year of his religious life. His death took place on the twenty-seventh of February, 1862, and he was buried in our retreat of Isola di Gran Sasso, Italy. “Being made perfect in a short space, he fulfilled a long time; for his soul pleased God” (Wis, iv. 13).

Heroism of Sanctity

Nothing has been said in the life of Gabriel of marvelous powers, of great deeds, or of astounding miracles; yet he was a hero of sanctity. We have four proofs of his heroism his life proves it; his fellow-men proclaim it; God testifies to it, and the Church defines it.

Gabriel’s life proves him to be a hero. Victory makes a man a hero, but self-conquest is the greatest of victories; therefore, Gabriel is a great hero, for he conquered self. There was not a fault, not an evil inclination in his nature, that by the grace of God he did not subdue and conquer. By nature he was impetuous and strongly inclined to disobedience; he conquered self by humble submission and blind obedience to superiors. By nature he was inclined to levity; he conquered self by a wonderful recollection at work, and by great constancy and fervor in prayer and meditation. By nature he was inclined to vanity, and was fond of dress; he conquered self by assuming the poor and humble habit of a Passionist. By nature he was much inclined to seek social pleasures, and the world promised him a brilliant career; he conquered self by burying himself in a monastery. The constant self-denial and sacrifice required to be present punctually at every act of the monastic observance, to fulfill exactly every point of rule, and to comply obediently with every wish of superiors, are, in the opinion of many, equal to martyrdom. Gabriel was punctual to the minute, and exact in every point, even the least. He was a hero of faith, for in all things he saw the will of God, and united himself to it by blind obedience. He was a hero of hope, for he looked to no one but to God for his reward, and never ceased to strive for it. He was a hero of charity, for he renounced self, he renounced home, he renounced the world, and did all for the love of God.

Gabriel’s life proves his heroism, and his fellow-men proclaim it. Nothing is more miraculous about Gabriel than the rise and propagation of devotion to him after his death. He was almost a stranger to the people of the Province where he died. He had been in their midst only three years. Their only opportunity to see and hear him was when he served Mass in the church, or sang in the choir. He never left the monastery except in the company of his fellow-students, and then he would not speak to strangers without permission from his director, who always accompanied him. The least frequented roads and the most solitary places are chosen for these walks beyond the monastery walls. Gabriel did not work a miracle, nor he did nothing extraordinary before his death. The people had seen little of Gabriel, but that little had deeply impressed them with a firm belief in his sanctity. The year after his death our religious were driven by iniquitous laws from the monastery where he was buried. For years the monastery was used by the Italian Government as barracks for soldiers, and for years it was abandoned and left without a caretaker. Yet, after thirty years, when a community of our religious returned, and once more took possession of the place, they found the people still frequenting the old church, and praying at the tomb of Gabriel, whom they called “The Holy Religious.” They gathered together and opposed an attempt to remove his body. They held meetings, and angrily asked why he was not proclaimed a saint. What gave these people so firm a belief in the sanctity of Gabriel? Who inspired them to visit his grave and to pray to him as to a saint?

It has been my happy lot to dwell for a few days in the retreat beside the tomb of Gabriel, and I shall never forget what I saw and heard there. Gabriel had lived and died there; Gabriel had stood there; Gabriel had gazed upon these scenes as I gazed upon them. I seemed to feel his presence; I seemed to hear his voice.

The church and monastery stand alone on a low hill, and face an amphitheatre of the highest peaks in the Apennines. About two miles off stands the town of Isola, called Isola, or Island, because it is almost surrounded by two little rivers that meet there. At the head of the valley, five or six miles away, stands the Gran Sasso of Italy. This is a mighty peak of bare rock, with a face almost as perpendicular as a wall. It tapers as it rises, and, reaching thousands of feet into the heavens, towers over every other peak in the Apennines. At each side of this huge and lofty rock the other mountains fall away in a semicircle until they become undulating hills. One day in the autumn of 1903–it was a Saturday–I stood at the window of a cell in the monastery, and gazed upon this magnificent panorama. It was a beautiful day. Now and then a few clouds floated over the clear heavens from the sea, and gathered to form a fleecy canopy over the high head of the Gran Sasso. Round the neck and over the shoulders of this mountain giant, where he unites with his fellow-peaks, lay a glistening white collar of purest snow. Dark, olive-colored pines grouped in forests in the lower ridges of the mountains and climbed up their sides. Their sombreness was relieved by the bright green firs that grew in their midst. Lower down the great beech forests were lighted up with brilliant autumn tints; the sunbeams slanting on them down the mountain sides gave them the appearance of a forest on fire. Between the sunshine and shadow of the hills and on their tops the herbage gleamed with a sheen like that of silver and gold. The grandeur and beauty of the scene enraptured me; green fields and waving forests, dark valley and glimmering hills, beetling cliffs, snow-capped mountain, and glorious Italian sky held me entranced. I could not tear myself away from them. My eyes feasted with raptured delight upon the lovely grandeur of Nature; I could not give them their fill. There was but one thing wanting a voice to praise the Creator a voice to cry out, “Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Hosts, the earth is full of Thy glory!” And lo! even as I gazed and drank in the wonderful beauties of the Creator’s works, I heard the music of voices growing louder and louder, and drawing nearer and nearer. They sang the praises of God, and chanted His litanies.

There are no railways and few coaches running over those hills and mountains. Travelers mostly go on foot there. Along the roads, and by the paths leading to the monastery and church, little bands of people, sometimes five or ten, sometimes twenty or thirty together, were approaching. There were grandfathers and grandmothers with a staff to help them, and with grandchildren, that ran before them on the way, and then sat down to await their coming. There were boys and girls; there were young men and their wives, all dressed in quaint and picturesque Italian costumes. Some had a mule or an ass laden for the journey; others carried their provisions and extra clothing in a bundle on the head. Almost everything is carried that way. The baby peeps out of a basket carried on the mother’s head. There, poised in the air, it is swayed to sleep, or gazes wonderingly at the heavens above, as the mother walks along, knitting as she goes. Who were these people? What brought them to the monastery? They were Gabriel’s fellow-countrymen; they were pilgrims to his tomb. Some of them came from the valley, others had come from beyond the mountains. Some of them had been a day, others two days on the way. They sang hymns and chanted litanies as they came. As soon as they entered the monastery grounds they took off their hats, and walked bareheaded to the front of the church. There each band of pilgrims grouped together, and finished the litany or hymn they were singing before entering the church to kneel at Gabriel’s grave and kiss his tombstone. Some came merely out of devotion to him; some came to beg his intercession for them with God; some came to do penance for their sins. These would make their way on their knees from Gabriel’s first resting place, near the door of the church, to his tomb at the other end near the altar, or would remain for hours in prayer beside the body of their “Holy Religious.” The simplicity and lively faith of these devout pilgrims brought tears to my eyes, and stirred my faith as it had seldom been stirred before. One could feel, and seemed almost able to touch, the supernatural in their midst. All that Saturday I stood at the window gazing at the scene before me. All day long the pilgrims continued to come. They came until the church, the sanctuary, and the sacristy were packed; until the large shelter built beside the church was overflowing, and until hundreds were camped in the fields outside. They stopped there all night. Ten of our Fathers heard confessions from early morning till late in the evening. Several times that night I was awakened by the tramp of feet and the singing of hymns beneath my window; more pilgrims were streaming in. The priests arose at two o’clock, and began again to hear confessions and celebrate Mass. Masses were celebrated until noon on Sunday, and confessions were heard until late in the afternoon. After going to confession, hearing Mass, and receiving Holy Communion, the pious pilgrims again gathered into bands, and started on their way homewards, joyfully singing and chanting as they went. That [was] a common sight at the tomb of Saint Gabriel during the months of summer and autumn. That is a people’s testimony to the heroism of his sanctity.

Above the proofs that Gabriel gave of his heroism, and above the declaration of the people, is the testimony of God. He sets His seal upon our hero’s sanctity, and stamps it as genuinely heroic by working miracles through his intercession. The following accounts of miracles are taken from a life of Gabriel by Father Nicholas Ward, C.P.:

“Mary Mazzarella, aged twenty, lived with her parents in the town of Isola. For nearly three years she had been suffering with serious complications affecting her lungs, stomach, and spine, with constant daily fever and headache. At first there seemed to be question only of gastralgia, or neuralgia of the stomach, but clear symptoms soon made it evident that acute tubercular phthisis, or consumption, had set in. Three hemorrhages ensued. Gradually losing all appetite, the physician allowed her to take anything she might fancy; but her daily food hardly amounted to two or three spoonfuls of the pottage prepared for the family. Her condition steadily became worse. In January, 1892, she experienced great pains all through her body, and six ulcerous wounds broke out. These wounds continued to enlarge, and prevented her from, resting either by day or night. From five of the wounds putrid matter was discharged. She became so weak that she could not stand on her feet, and was unable to bear the light. The summer heat inconvenienced her greatly, so that she could hardly breathe; then loss of sleep, joined with the constant oppression on her chest, so affected her voice that she could speak only with difficulty. The remedies used were of no avail, and she lost confidence in medicine. In August she was persuaded to allow Dr. Tattoni to attend her. After a careful examination, he declared the case hopeless. Finally, she turned to heaven for her cure, and, with all the confidence and tenderness of a loving child, besought her Blessed Mother to help her. Now, it happened that one day in October, having fallen asleep, she saw a beautiful lady with a child in her arms, and she was told to go and pray at the tomb of the young Passionist at the monastery, and use some of his relics that she might be cured. At the request of her uncle, Father Germanus, Passionist, went to see her. This is what he says: ‘When first I saw her I was seized with horror. She seemed to me like a corpse, the only sign of life being a slow and painful breathing. Propped up with pillows, she was lying motionless, tormented with six large purulent ulcers, that gave her no rest by day or night. It was then three months since she had taken solid food, and I remember saying on that occasion that, if the Blessed Virgin cured her, it would be a miracle like the resurrection of Lazarus.’ This visit took place two days after the patient saw in her sleep the vision of a beautiful lady and child. Father Germanus did not believe the story of her vision. He said that we should not tempt God, that the patient should not be put to the discomfort of being taken to the church, that the journey might hasten her death, and that if the Blessed Virgin were willing to obtain for her a cure, she would do it without the journey at all. The girl herself informs us: ‘Father Germanus came to see me on October 20th. He put about my neck a crucifix belonging to Confrater Gabriel, the servant of God, and he put on me also the leathern girdle that was taken out of his grave. The Passionist Father greatly comforted me, exhorting me to have confidence in the intercession of this holy religious. He told me to make a vow to go barefooted to the monastery church in case the favor should be granted, assuring me that after three days of prayer, made with my heart rather than with my lips, I would obtain my cure. Meanwhile the malady did not abate, but I recommended myself the best I could to Confrater Gabriel. The triduum was to finish on Sunday, October 23d. Saturday evening I felt very, very sick, and my people at home were more than usually downcast, for when they carried me to my room they had great trouble in undressing me and getting me ready for bed.’ So far poor Mary’s account. We learn from other sources that her family’s anxiety was even greater that night than she imagined. Her mother, who had no longer any hope of her daughter’s cure as the result of the triduum, and fearing, besides, that the girdle might inconvenience her, was about to take it away, but Mary objected, saying that the whole night was still wanting to complete the three days.

“ ‘Towards the first dawn of the following day, Sunday (to resume Mary’s own narrative), I told my sister to recite the Litany, and to join me in praying to the servant of God. While I was saying the litany there came upon me a quiet sleep, such as I had not had for a long time. After a while I awoke full of joy, feeling that I was cured completely cured. My strength had returned, the sores were closed, and one of them, which was very large and about to open, disappeared altogether. Filled with delight, I say to my sister, “Get up! I am cured! Confrater Gabriel has done this miracle for me!” For well-nigh eight months I had been unable to wait upon myself; my people had to assist me in everything. Now, that morning I got up at once, dressed myself in haste, and went down to the kitchen. My sister would not believe her eyes; she kept by my side, afraid lest it all might be a delusion. But I went downstairs, and stood before my parents and the servant-maid, who were all in the kitchen. My mother was astounded when she saw me, but I said to her: “Mamma, don’t be afraid; Confrater Gabriel has performed the miracle for me;” and to reassure my poor mother all the more, I took the baby from her arms into mine.’

“Now, it happened that the feast day of Isola was celebrated on that Sunday, and there was in the town an extraordinary concourse of strangers. Mary’s father, beside himself with emotion, ran out of the house weeping. The neighbors crowded around, thinking that his daughter had just died; and, lo! there was Mary among them sound and happy. All were deeply moved, and wept for joy. That same morning Mary went to the parish church with her parents, heard Mass, and received Communion. The next day she went to the sanctuary of Our Lady of Favors outside of the town; and on the following Tuesday–that is, October 25th–two days after her cure, together with all her family, all barefoot like herself, and accompanied by the whole population of Isola, she went to fulfil her vow at the tomb of God’s servant. She walked all the way, going and returning, a distance of about five miles, and has enjoyed perfect health ever since. This cure has been attested by the sworn statements of Mary herself, her parents, Father Ciaverelli, the two physicians, Dr. Tauri and Dr. Rossi, and several others.”

“One evening in June, 1893, there came from Acquasanta to the retreat of Isola a cripple named Anthony Mancini, who for many years had lost the use of his limbs in consequence of an obstinate arthritis. As the disease had crippled him in a frightful manner, the physicians attempted to straighten him by breaking the joints of his thighs and knees; but this only completed his ruin, and deprived him of all hope of ever being able to take another step. Besides, the poor man was wasting away through muscular atrophy, so that he could no longer move his body, and was forced to spend his days seated in an arm-chair, from which he had to be lifted into bed at night.

“Seated thus, and even bound to his chair (lest the motion of the wagon should throw him off), he arrived after a long journey, at the Passionate Church. All who saw him were touched with deep compassion, and as he was moved from the wagon, and carried to the tomb of Gabriel, many joined with him in prayer, asking his cure from God. During the night he was given lodgings in the abandoned retreat, and the next morning he was brought in his arm-chair into the church to Gabriel’s sepulchre. After the parish priest of Isola had heard his confession and given him Communion, the poor man continued his prayers to the servant of God. All at once, in the sight of all the people, Anthony arose from his chair cured, exclaiming: ‘Gabriel, the servant of God, has granted me the favor!’ Leaving his chair behind him in the church, he got into his wagon unassisted, and joyfully turned his face homeward, blessing God. The people of the villages and towns through which he had passed on his way to Isola, and who had seen him in so pitiful a state, were now speechless with surprise on beholding him hale and hearty, and every now and then he had to stop to satisfy their curiosity.”

“Not less extraordinary was the case of Cajetan Mariani, of Amatrice. In consequence of a stroke of apoplexy, he was paralyzed for twelve years in his whole body, so that he could barely drag himself around with the help of a stick. He was seventy-one years old, and entertained no hope of a cure; still less did he think of praying, for he had lived estranged from God for a long time. One day, by some unaccountable impulse, he desired to go to Isola. As he entered the monastery church he saw a priest hearing confessions, and asked to be heard himself. The bystanders were greatly astonished at this, because they knew him well. Greater still was their wonder when they saw the old man making his confession with an abundance of tears. A few days afterwards, continues the priest to whom we are indebted for these facts, ‘as I returned to the church, the man came up to me quite joyfully, his eyes moistened with tears, and said: “Oh, Father, this dear servant of God obtained three great graces for me; he touched my heart and brought me back to God. I have prayed and felt myself cured all at once of my paralysis, so that I am well and can walk about with ease, you see; besides, I was afflicted for many years with rupture; this, too, has disappeared this very hour. What shall I do to show my gratitude to God for so many blessings?” ’

“Whatever the enticing advertisements in our daily papers and circulating pamphlets, medical science tells us that the radical cure of rupture (hernia) is seldom accomplished except by operative surgery, and not a single instance has ever been recorded of instantaneous cure of hernia. Now, we read in the processes that Gabriel has declared himself by facts to be the special friend of the ruptured, and in 1897 we find on the register about ninety cases of complete and instantaneous cure.”

Gabriel was a faithful servant in a few things, and now God makes him the dispenser of many graces and blessings. The miracles recorded are but a few of the many wrought through his intercession. By visits to his tomb, by prayer to him, and by the use of his relics, the sick have been cured, the blind have been made to see, the dumb to speak, the deaf to hear, and the crippled to walk. Not one-half the miracles worked by God through His servant are kept on record, and still up to the present [before or as of 1917] over four hundred have been recorded. […] The dying, restored to life through having recourse to him, have left there the coffins that had been prepared for them. Cripples have left there their chairs and crutches. Hundreds of immense wax candles are stored there. High cases with glass doors line the walls, and are stocked with costly church vestments, and all kinds of gold and silver church plate and ornaments. Some have left their earrings there, some their rings, and some their watches, bracelets and chains. These are numbered by the thousand; each is an offering in thanksgiving for something Gabriel has done for the giver. And this wonder-worker was only twenty-four years old when he died! He was less than six years in religion! He [was then] not yet fifty years in the grave! One of his brothers [was] still alive! Oh, wonderful are the ways of God! We seem to hear Him saying: “Well done, good and faithful servant, because thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will place thee over many” (St. Matth, xxv. 21).

Beatification

The Church has carefully weighed the evidence in favor of Gabriel’s heroic virtue, and minutely examined the miracles that testify to it. She has now added her testimony to that of others. In 1896 she bestowed upon Gabriel the title of “Venerable.” On the thirty-first of May, 1908, she went a step further by publicly announcing his beatification and giving him the title of “Blessed.” The London Tablet in its account of that impressive ceremony said: “The last of the three beatifications fixed for the Jubilee year of Pius X was held today in St. Peter’s. They have brought us very near the saints. . . . Rarely, if ever, in the history of beatifications did heaven and earth seem brought so close to each other as this morn when the curtain fell and the figure of Blessed Gabriel of the Virgin of Sorrow shone out amid the radiance of innumerable lamps above the chair of St. Peter. He looks down upon those to whom he owed obedience, respect, and love on earth, whose hands he had clasped but [then] a few years ago. There was his elder brother, Dr. Michael Possenti, still in the flesh, still vigorous and active in the medical profession at the age of seventy-three. As he looks from the raised tribunal near the altar at the picture of his younger brother amid a band of angels, recollections of their boyhood in their old home mingle with the deep Catholic spirit of veneration and humble prayer, that unites the vast multitude gathered about the tomb of the Apostles to hear the word of Christ’s Vicar proclaiming a new hero and intercessor in the Church of God. The doctor’s daughter, a niece of Blessed Gabriel, is with him. An old school companion of Gabriel’s is now a prosperous tradesman in Rome. Needless to say, he was also present this morning. Another human touch to this wonderful scene. Among the crowd of worshippers is the lady whom the parents of Gabriel, in their earthly plans for his welfare, destined him to marry. She is now the wife of an Italian colonel. There is also present a person whose miraculous cure has served for the process of beatification. Above all, Father Norbert, is here. What a joyous day is this for him, the Novice-Master, the teacher and spiritual director of Gabriel! He is now seventy-nine years old, and he comes to see his former penitent, who used to come to him for absolution and advice, exalted to the honors of the altar. It was Father Norbert who assisted Blessed Gabriel on his death bed, and witnessed every stage of that perfect closing of his life.”

Canonization

Before those who are beatified can be canonized and called saints, it must be proved that at least two more first-class miracles have been performed by their intercession after the date of their beatification. This condition was soon fulfilled in the case of Blessed Gabriel. Almost daily we hear and read accounts of miracles wrought for those who appeal to him for intercession with God. When two of these miracles had been proved to the satisfaction of the careful and exacting judges appointed to receive evidence and examine witnesses, Pope Benedict XV was petitioned to canonize Blessed Gabriel. This petition was made in 1918 in union with the petition for the beatification of Venerable Oliver Plunket. On that occasion the Pope said: “The decree which approves the two miracles attributed to the intercession of Blessed Gabriel is a new stimulus from on high urging us to more effectually imitate the virtues of this dear son of Umbria, to whom, as a new Gonzaga, can be applied the words of Holy Scripture, ‘being made perfect in a short space, he fulfilled a long time.’ The short space of time from the day of his beatification to the two wonders attributed to this young Passionist is clear proof of heavenly designs. This will appear in a clearer light to any one who considers that the publication of the decree in relation to Venerable Plunket, and the reading of the decree in regard to Blessed Gabriel teach one lesson, namely, that the perfection of a Christian depends upon the diligence and constancy with which he discharges the duties of his state. And this rule of conduct should not appear to any one too vague because general, nor too simple because easy. Its true worth lies in the fact, that it embraces all conditions in which a Christian may be placed, and no one can reject it as being too difficult for the ordinary man.” These words of the highest authority on earth remind us that saints are raised up by God not merely to intercede with Him and obtain miracles for us, but especially to be models of virtue for our imitation. This truth is often forgotten by those who make no effort to walk in the footsteps of the saints and imitate their virtues, and who seem to think that a saint is of no use unless he works miracles for them. It was not the virtues that appeal to the world, the virtues of a public, popular life, that raised Gabriel to the heights of sanctity; but the virtues of the hidden, interior, spiritual life, the virtues practiced by Christ in the humble home of Nazareth. These virtues–a whole-hearted love for God, a fervent practice of religion, purity of intention, humility, obedience, poverty, chastity, self-denial, penance, prayer, fraternal charity, and a constant remembrance of the Presence of God in union with Jesus and Mary may be practised in every state of life. They sanctify the servant as, well as the master. They are more easily acquired and practised by the poor than by the rich. They make saints of laymen as well as of monks and priests. A writer, already quoted, commenting on the beatification of Saint Gabriel said: “The Church has judged Blessed Gabriel by the same criterion she has applied in the case of those saints whose works have earned renown and stirred the world. There is no space reserved in the Book of Life to record that the servant of God cast out devils in Christ’s name, or built churches, or founded institutions, or wrote remarkable books, or initiated successful schemes for the betterment of the toilers and the poor. These things may or may not count, according to the spirit which pervaded them. It is the interior life which matters. And it would be difficult for the Church to teach this in a more emphatic way than she has done by the solemn act of Beatification today. The man of science eliminates one element after another in the chemical compound before him, until he has found the essence which he seeks in his analysis. So does the Church in her investigation of the life and work of a servant of God look for the presence of the pearl of great price–interior holiness in the heroic degree. It would seem that in Blessed Gabriel of the Virgin of Sorrows it lay bare and open to view unmixed with other elements.”

The canonization of Saint Gabriel, in union with that of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, took place in St. Peter’s at Rome on Ascension Thursday, May 13, 1920. The decrees were published by Benedict XV in the presence of forty-five cardinals, two hundred and eighty bishops, and a devout multitude of over thirty thousand worshippers who gathered there to do honor to God and His saints. Brother Silvester, a Passionist, who had been in the Novitiate with Gabriel, was there, and Dr. Michael Possenti, in his eighty-sixth year, was also there to see his saintly brother receive the highest honors that can be paid to a man on earth.

Conclusion

No better conclusion can be put to the life of Gabriel than that of the correspondent to the Tablet just quoted. Little remains to be added.

One of the religious, standing beside Gabriel in his dying moments and seeing his holy death, struck his breast and said: “So many years am I in the service of God and yet so backward; while he in so short a time became a saint, and has had such a beautiful death.”

So many years we have been on earth; so many years we have known God; so many years we have been in His service; and why are we so backward? Why are we not what Gabriel was? Because we do not correspond with God’s grace; because we do not make use of the daily opportunities given us to serve Him; because we neglect, or carelessly perform, the work that He puts in our hands.

“Lives of great men all remind us we can make our lives sublime.” The life of Gabriel reminds us we can make our lives sublime, and tells us how to do it. We shall ennoble life and make it sublime, not by idly dreaming of mighty deeds that we shall never be asked to do, not by vainly longing for opportunities that may never be given us, but by making the best use of present opportunities to do good, by faithfully performing the ordinary daily duties of our station in life, whatever it may be, by doing with all our might whatever the hands find to do, by taking up our daily cross and following Christ, and by doing all for the love of God. Whoever does this will apply to himself the lesson of Gabriel’s life, will sanctify his soul, will make his life sublime, will store up great merit in heaven, and will surely hear from God the words of praise and reward: “Well done, good and faithful servant, because thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will place thee over many things; enter thou into the joy of thy Lord” (St. Matth, xxv. 21).

Taken from: St. Gabriel of Our Lady

of Sorrows, Passionist, A Youthful Hero of Sanctity, by Rev. Fr. Reginald Lummer, C.P., Edition 1920, Imprimatur;

Saint Joseph Daily Missal, Imprimatur

1957.

Related Links

–

1. The

Holy Season of Lent.

2. Laws

of Fasting and Abstinence.

3. Perfect

Contrition.

4. The Seven Penitential

Psalms.

5. Devotion to our

Lord’s Passion.

6. Devotion

to our Lady’s Sorrows.

St. Gabriel Possenti of Our Lady of Sorrows, pray for us.