January 31, 2021: ST. JOHN BOSCO

January 31, 2021: COMMEMORATION OF ST. JOHN BOSCO, CONFESSOR

“Blessed is the rich man that

is found without blemish… Who hath been tried thereby, and made perfect, he shall have glory everlasting. He that could have transgressed, and hath not transgressed: and could do evil things, and hath not done them: Therefore are his goods established

in the Lord, and all the church of the saints shall declare his alms.”

(Ecclus, xxxi. 8,10,11)

Prayer (Collect).

O God, who comfortest us, by the yearly solemnity of blessed John, thy Confessor; mercifully grant, that while we celebrate his feast, we may imitate his actions. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, thy Son, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God, world without end. Amen.

Works of St. John Bosco

“A tender love for his neighbor is one of the greatest and most excellent gifts that Divine Providence can bestow upon man.”

The spirit of these charming words of St. Francis de Sales, inscribed at the head of the Salésian Bulletin, is truly characteristic of this work and the man of this work.

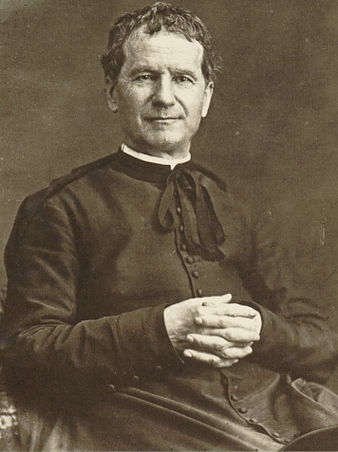

No one can see Don Bosco without feeling attracted to him, or without loving him at once, for his heart is all love, and the divine light of a tender love beams in his countenance.

Like St. John, the beloved disciple, leaning on the heart of the Master, inebriated with ineffable delight and exclaiming: “Lord, I love Thee,” so Don Bosco, taking to his heart this multitude of children to whom he became a father, sends forth a sigh of love which assuredly ascends to the feet of Him who said, “This is My commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you.”

The Abbé Don Bosco founded the Society of St. Francis de Sales, the object of which is to devote itself to the different works of piety and charity, and in particular to the special care of poor abandoned children upon whom depends the future happiness or misery of society.

Poor abandoned children! Could there be a more admirable work than that of taking special care of children whom neglect, ignorance, and contact with depraved, perverted natures defencelessly expose to the snares of evil?

Don Bosco gathers them together, gives them an asylum, teaches them an honorable trade, makes them useful citizens; but above all, he ennobles them, as it were, by initiating them in the splendors of revealed truth. He teaches them how to appreciate the immortal beauty of that soul made in the image of God, which they outrage through ignorance. Many of these children of the people have been raised to the highest dignity with which man can be invested: they have become priests!

We shall see how Don Bosco received the first inspiration of the mission which Divine Providence was to confide to him.

Elevated to the priesthood in 1841 at the age of twenty-six, instead of accepting the places offered to him he resolved to remain for a time at Turin under the immediate guidance of his compatriot and spiritual director, the Abbé Cafasso, then President of the Conference of Morals and Director of the Ecclesiastical Institute of St. Francis of Assisi.

Don Bosco had unbounded confidence and veneration for this worthy priest. He submitted to him all his actions and deliberations, and entered this Institute, the object of which was to perfect young priests in the knowledge of practical morals, and in the exercise of preaching.

The influence of this house was most favorable to the expansion of the soul; the inmates studied, but above all they prayed: yet this did not exclude an active participation in exterior works of charity, such as visiting the poor, the sick, the hospitals and prisons.

Don Bosco was introduced by his master into the prisons of Turin. The young priest was deeply moved at finding in the prisons great numbers of young boys, and even children.

He was filled with horror and pity at their precocious depravity, the cause of which was too evident, as from their birth these poor children were completely abandoned, and had always before their eyes a deplorable example of vice. They broke the law, and society, considering them injurious to the community, must needs imprison them. But far from bettering their condition, their sojourn in prison only rendered them still more corrupt.

From that time he labored unceasingly, impelled by an invisible impulse to devote himself to the poor abandoned children who crowded the streets of Turin. He resolved to snatch them from the evil influences to which they were a prey, and to teach them to know, love, and serve the God who died for them and of whom they had never heard. While contemplating this great object which he had so much at heart, an unforeseen circumstance, or rather the hand of God Himself, brought him his first neophyte, Barthelemy Garelli d'Asti, an orphan sixteen years old, who, like so many others, lived abandoned in the streets of Turin.

He entered by chance the sacristy of the church where Don Bosco was vesting for Mass, and the sacristan, who was at that moment looking for some one to serve the Mass, readily seized the boy.

Garelli was at a loss how to render such a service, and as he refused to comply with the somewhat blunt request, the sacristan gave him a sound box on the ear, which made him cry out.

Don Bosco was attracted by the noise and disturbance, and when informed of the cause he comforted and petted the boy and coaxed him to remain and hear Mass, after which he talked with him, asking him many questions.

He was horrified at the boy's perfect ignorance of the first rudiments of religion, and that same evening began his religious education by teaching him the sign of the Cross.

Thus was the Œuvre Salésienne begun on the beautiful feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin, the 8th of December, 1841.

O Queen of Heaven! what graces have you not obtained since then for Don Bosco and his children!

Having noticed the effect of harsh treatment on the first child sent him by Providence, Don Bosco was from that moment fully convinced that children should always be treated with extreme gentleness. This exquisite gentleness, amounting even to tenderness, has become the motto and spirit of the Salésian Society.

The instruction in catechism given to Garelli soon attracted several of his comrades, and though mostly masons’ apprentices, bound when very young to masters who took no care of them, it is worthy of notice that from this time none of the children fell victims to those accidents so frequent in their rude and perilous trade. At the beginning of the year 1842 Don Bosco found himself in charge of a hundred children and youths, to whom he taught the principles of religion. He collected them together as often as possible, and took them to Mass and Vespers. He even succeeded, but with some difficulty, in forming a small choir, whose singing added much to the attraction of the reunions. When he could, he never failed to procure for them some material gratification. He also visited them in their workshops, and when he found any of them out of employment he scoured the country till he found them good masters.

The Institute of St. Francis of Assisi, with its modest chapel and adjoining sacristy, was the first asylum offered to these children. From the beginning Don Bosco gave to the reunions the name of the Oratory, thus markedly showing that prayer was the sole power upon which he relied; he also from the commencement placed himself and all his children under the immediate protection of the Blessed Virgin.

In 1844, when Don Bosco, having finished his studies at the Institute of St. Francis of Assisi, was now about to assume the more decided duties of the priesthood, several positions were offered to him, but as usual, wishing to give up his own will, he confided this important decision to his director, the Abbé Cafasso, whom he considered as the interpreter of the Divine Will in his regard.

His inclinations led him to devote himself more and more to the children whom he loved with a tender love, but, with a detachment worthy of admiration, he was willing to go wherever Almighty God sent him. After much prayer and reflection, the Abbé Cafasso appointed him director of the little hospital of St. Philomena. He assisted also in the direction of a Refuge for young girls, established in the neighborhood by the Marquise Barolo.

This new position seemed at first entirely incompatible with the development of the little Oratory, but it was really most favorable to it.

In the Abbé Borel, a priest of French origin, then director of the Refuge, Don Bosco found a friend such as Almighty God gives only to His elect, and one who proved an incomparable aid in the work for the children. As soon as these two priests met, it seemed as if they had always known each other; their love was mutual, and they went resolutely to work like old friends.

The little room allotted to Don Bosco at the Refuge was the meeting-place for the children, who soon numbered more than two hundred. As the place was absolutely incapable of accommodating all, they filled the stairs and halls, and the state to which Don Bosco's poor little cell was reduced may be imagined. But a more serious grievance was that, even with the assistance of the Abbé Borel, he could not manage to hear all their confessions on the eve of certain feasts.

In this dilemma he applied to the Archbishop Franzoni, who approved and blessed the work. At this high recommendation the Marquise Barolo hastened to place at their disposition two rooms in the hospital, which they converted as best they could into a chapel. Here, on the 8th of December, 1844, the feast of the Immaculate Conception, Don Bosco said Mass for the first time, surrounded by his children. The work advanced under the manifest action of Divine Providence. At this time Don Bosco gave his Oratory the title of St. Francis de Sales.

He was guided in this choice by several circumstances. The material one was that the Marquise Barolo, having intended to found a congregation of priests under this title, had destined the very rooms which she gave to the Oratory for this purpose, and with this idea she had a picture of St. Francis de Sales painted at the entrance. In the second place, Don Bosco had long since recognized the unalterable sweetness and exquisite gentleness of St. Francis de Sales as the surest means of reaching the hearts of children. Moreover, several heresies had noiselessly glided into the city of Turin and threatened to disturb the faith of the people.

The work then became The Oratory of St. Francis de Sales, and this is why the family of Don Bosco bears the name Salésian.

But in order to rest on solid basis, all foundations must pass through trials and even persecution; for the road of the Cross is the only one that leads to life and truth.

These trials and persecutions were all the more sad and painful that they were sometimes instigated by wealthy people, and even by good Christians. Alas! The surest friendships are not always to be trusted: it is the old story, constantly repeated, of St. Peter denying his Master. We will show how this opposition manifested itself, and how Don Bosco bore himself through these difficulties.

The Oratory of St. Francis de Sales began to be definitely established. Catechism, singing of the canticles, instructions, interspersed with striking examples, interesting stories, and various games, filled the time of the reunions. Besides this, Don Bosco established night schools, which were soon attended by numerous adults, who after their day's work received elementary instruction very valuable to them.

But just at this time the Marquise Barolo reclaimed the place she had lent them, which she wished to use for another object. Don Bosco, through the Archbishop, obtained from the municipality the use of the Church of St. Martin.

This place was not very suitable for their purpose. Mass could not be celebrated in the church, which had long been abandoned, and there was no place for recreation except a small park in front of the church.

Nevertheless the Oratory was transferred to the place assigned it, and we give here the memorable words of the Rev. Abbé Berol on this occasion: “My children, cabbages will not grow into fine large heads unless they are transplanted; it is then for our good that we are transplanted here.” This good was not very apparent, but the ill-fortune was cheerfully accepted.

Three hundred children at play are noisy: it could hardly be otherwise. The people who lived in the houses facing the park which had become the playground, were soon annoyed by this unusual racket, they entered a complaint, and the municipal authorities notified Don Bosco that he would have to go elsewhere.

The municipality, however, far from being hostile to this work, even showed interest in the establishing of the night classes, and readily accorded Don Bosco the use of the church of St. Pierre-ès-Liens. Adjoining this church, so appropriate to the religious ceremonies, was a vast court just suitable as playground for the children, and a large vestibule served as a study-room, so that this change seemed for the best.

Alas! the next morning the rector who occupied the parsonage, annoyed by the noise of the children, and fearing the quiet he enjoyed in this retreat might be disturbed, made such a bitter complaint that the permission granted was immediately withdrawn.

Meeting in Don Bosco's cell was utterly impossible, and for two months the Oratory had to hold all its exercises in the open air.

On Sundays and feast days from early morning the children in great numbers gathered around Don Bosco, the new Moses, who conducted his little people to some church in the outskirts of the town, where he said Mass for them. Each one brought some provisions—not a repast of three courses, it is true, nor did they have three meals a day, but their appetites were incomparable. After a summary breakfast they had Catechism in the open air, and then instruction. They finished the day by a promenade, and returned in the evening to the city singing canticles, awaiting the promised land under the form of some sort of shelter.

This existence, full of sentiment from a certain point of view, became impossible as the cold season approached. At the beginning of winter Don Bosco had to rent three rooms in the Moretta House, situated almost in front of the place where now stands the sanctuary of Our Lady Help of Christians.

But the time of rest had not yet come, and impediments to the work constantly occurred one after another. First, the Marquis de Cavour, then chief of the municipal police of Turin, pretended to see in these inoffensive reunions a political object, dangerous to the state. He wished to have them suppressed, and all the energy of Don Bosco was needed to escape this serious difficulty.

Even the clergy of Turin joined Cavour's party. Some of them saw with jealousy a work established in which they had no share, and the cures claimed that their churches would be deserted.

The reply to this was very simple: since nearly all these children were strangers in the city, the greater part of them having neither hearth nor home, they consequently belonged to none of the parishes. Was it then a crime to withdraw them from the dangers of the street, and thus make valuable recruits for the Church?

This misunderstanding was no sooner settled than the lodgers in the Moretta House, where they held their meetings, complained so much of the noise made by the children, and of the inconvenience they caused, that the landlord rudely dismissed them, and they were once more in the street. This was in the spring of 1846, and the weather was beautiful. “Almighty God,” thought Don Bosco, “treats my poor little children as well as He does the little birds.” Not being able to find a house, he rented a meadow.

The Installation was so primitive at this time, that it forcibly recalled Our Lord wandering through the small towns of Judea, followed by His disciples, and with only the starry vault of heaven for shelter.

On Sunday the children came early, and began the day by going to confession to their Father; and certainly the mode of confession used in the Salésian family reminded one by its touching simplicity of the relation between father and son.

The priest's seat was a grassy mound; beside him knelt the little penitent, the arm of the priest lovingly encircling the child, while its head rested upon his heart. How sweet and easy the avowal of faults thus became!

Having no bell, the young battalion was assembled by a drum and trumpet found nobody knew where, and which would have delighted a lover of antiques. All the rest of the installation was to come. But what good he accomplished in this humble asylum! what charming, touching instructions penetrated the hearts of the children! What earnest and fervent prayers ascended to heaven!

The children were first taken to a neighboring church to hear Mass; then they breakfasted as best they could, and returned and spent the day in this pleasant meadow of Valdoco, where lively games judiciously alternated with instructions and spiritual exercises.

Alas! Don Bosco was soon unfortunately deprived of this meadow. The owner claimed that the tramping of the children destroyed the roots of the grass, and he notified them that they must leave.

The better to prove the instability of all human support, Don Bosco just at this time lost his position of Director to the Institute of the Marquise Barolo, and the emoluments thereof which were almost his only resource.

When this occurred, his friends and even Rev. Abbé Borel urged him to give up his care of the children. “Keep only twenty of the smaller ones and send the others away: you cannot accomplish impossibilities,” they said; “and Divine Providence Himself seems clearly to indicate to you that the work is no longer to continue.” “Divine Providence!” replied Don Bosco, raising his hands to heaven, while his eyes shone with surprising brilliancy, “sent me these children, and believe me, I will never send one away. I am firmly convinced that He will provide all that is necessary to them, and since I cannot rent a home, I will build one with the aid of Our Lady Help of Christians. We will have large buildings, capable of receiving as many children as will come; we will have all kinds of workshops, that they may learn whatever trade they wish; large courts and gardens for them to play in; finally, we will have a chapel and numerous priests to instruct the children, and to take special care of those among them who show signs of a religious vocation.”

At this time it was supposed that Don Bosco had partially lost his reason; he was looked upon and pitied as one demented. This idea was confirmed by the minute description which he gave of his future Oratory, the plan of which evidently existed in his mind. He gave the description and dimensions of the chapel, the workshops, the dormitories, the class-rooms, the courts and gardens; and all conceived in proportions so vast and so little in keeping with his resources, that his mental derangement seemed no longer doubtful.

His friends gradually fell off; even those who seemed the most devotedly attached to him left him.

This belief in his mental aberration became so confirmed that they wished to confine him in an insane asylum.

We shall see later how the effort to carry out this idea resulted in the confusion of those who attempted it.

The day arrived when the children were to assemble for the last time in the meadow. The next morning it was to be given up to the owner, and Don Bosco knew not where he could assemble his dear little ones on the following Sunday.

It was like the Station at the Garden of Olives. Their countenances expressed deep dejection, and their cheeks bore traces of bitter tears.

The children saw him prostrate on the earth, and heard him cry out, “My God, may Thy holy will be done! Wilt Thou abandon these orphans? Inspire me how to find an asylum for them!”

Scarcely had he finished this prayer when a man named Pancrazio Soave approached him and asked, “Monsieur l'Abbé, are you looking for a laboratory?”

“Not a laboratory, but an oratory.”

“No matter; I have what you want. My godfather, Pinardi, who is a very honest fellow, has a splendid shed to rent, exactly what you want.”

What a providential opening! Don Bosco hastened with Pancrazio to the place indicated.

The shed was a structure of rare simplicity; no missionary among the savages could possibly have a ruder or more comfortless abode. The roof was so low that in certain parts one could not stand up without stooping, and the adjoining buildings were scarcely any better.

“It is certainly very low,” said Don Bosco. “My children are not very tall, but they would find it difficult to lodge here.”

“Is that all?” replied Pinardi. “I can have the soil dug down as deep as you wish; I will make a board floor, and you will have a little palace. Know, too, that I am a singer, and I will assist you by chanting at the services. I also have a beautiful lamp which I will lend you for your chapel.”

Touched by such good-will, Don Bosco asked, “Could you lower the floor a foot and a half?”

“I will see that it is done.”

“By next Sunday?”

“By next Sunday.”

“You will allow me the use of the surrounding grounds?”

“You can have the use of them.”

“How much?”

“Three hundred francs a year.”

“I will give you three hundred and twenty francs, but I must have a lease.”

“I will give you a lease.”

“Then I will take it.”

The affair concluded, Don Bosco returned to his meadow, and the setting sun lit up a very touching scene.

The poor children learned with great delight that Divine Providence had provided for them an asylum, and heartily cheered this shed of Valdoco which they were never to leave; for on this very spot was afterward built the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales as it now stands. They immediately repeated the Rosary in thanksgiving, and there could be no doubt of the fervor with which it was said.

Pinardi, assisted by Pancrazio and several workmen, accomplished wonders. In a week, as he had promised, the shed was made much more presentable, and on the following Sunday, the 12th of April, 1846 (it was Easter Sunday), they not only took possession of their new place, but were able to celebrate Mass and Vespers there. The shed, the floor of which had been lowered and covered with boards, made, with the addition of a coach-house, quite a good chapel, and all the adjoining ground served as playground for the children. The Bishop at once gave permission to say Mass and have all the religious exercises, Benediction, sermons, and novenas in the chapel. Soon there were seven hundred children in the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales du Valdoco, and the work took a decidedly encouraging start.

This success brought back to Don Bosco several friends who had recently deserted him, and attracted to him new assistants and valuable adherents.

The days were well filled at the Oratory. On Sundays and feast-days the chapel was open not only to the children, but to all in the neighborhood, who eagerly flocked to the modest chapel, which proved a blessing to this locality, inhabited by a very depraved class. An unhoped-for transformation may be said to have dated from this time.

Confessions were heard till eight or nine o'clock in the morning; then Mass was said, Don Bosco always preaching a very interesting sermon on the Gospel of the day, adding examples taken from Sacred Scripture.

Then came recreation, followed by a class till noon. At two o'clock, Catechism, the Rosary, Vespers of the Blessed Virgin, another instruction, and singing of the Canticles.

All this was made so attractive, that when evening came the children were very loath to go away, and it was necessary to turn them out. They went off, calling “Goodby, Father; good-by till Sunday.”

The good Don Bosco was generally so exhausted by his labors that he could scarcely drag himself home: but his strength seemed to be renewed by labor; so he hastened to definitely establish the night-school, which he kept open every night in the week.

The young men attended in large numbers; the great difficulty was to find teachers to help him with the classes.

This great need inspired Don Bosco with the ingenious idea of creating scholarships.

He selected the most talented young men, and offered to give them a complete course of instruction on condition that they would in their turn teach others.

Teaching is one of the best means of learning, and this institution of scholarships succeeded beyond all expectation.

He not only thus secured excellent and zealous teachers for his classes, but they became themselves a nursery of young priests, vocations developing among them at the same time with their instruction.

Don Bosco deserves much praise for the establishment of these night-schools; Turin and several other cities recognizing their excellence, hastened to establish similar institutions.

Nevertheless, the Marquis de Cavour, chief of the municipal police of Turin, again raised a formidable opposition, and he would doubtless have succeeded this time in having the Oratory closed if an unexpected protector had not arisen. The Count de Collegno, former Minister of State and Counsellor of Charles-Albert, declared that the king did not wish Don Bosco to be disturbed. The priest and the soldier, both men of action and devotion, always perfectly understood each other, and on more than one occasion the king testified his interest by gifts. Once especially, on the 1st of January, he sent three hundred francs with this superscription, “For Don Bosco's Little Rogues.”

Some idea may be formed of the overwhelming labor accomplished by Don Bosco, when we consider that besides the great amount of time given to his Oratory he still managed to exercise his ministry in the prisons, the Cottolengo Hospital, at the Refuge, and also to visit the sick in the city. Moreover, he wrote for his children several works, the principal of which are “Sacred History for the Use of the Schools;” “Youth Instructed,” a valuable work, which has gone through more than eighty editions; “The Metric System of Decimals;” “The Seven Dolors of the Blessed Virgin;” “Devotion to the Angel Guardian;” “Exercises on the Mercy of God;” “History of Italy;” “Abridged Ecclesiastical History;” etc. As no constitution could endure such labors, complete exhaustion soon reduced him to a very alarming state, and he was obliged by the imperative commands of the physician to retire for some time into the country. Here he should have taken a perfect rest, but the frequent visits of his children, together with the pupils and Brothers, left him no repose. Moreover, he returned to the city Saturday evening to hear confessions, and to assist at the reunions at the Oratory on Sunday.

In July, 1846, when making one of these journeys from the country, he took a cold which resulted in a severe inflammation of the lungs, which his poor exhausted body was little able to sustain.

The danger increased so much that the physicians lost all hope.

One night, which threatened to be his last, the Abbé Borel said to him, “Don Bosco, ask Almighty God to cure you.”

“No,” he replied, “I must abandon myself to the will of God.”

“But you cannot leave your children; I beg of you, in their name, to ask God to cure you.”

Then the poor sufferer, to gratify his friend, murmured, “O Lord, if it is Thy good pleasure, grant that I be cured! Non recuso laborem.”

“Victory!” the good Abbé exclaimed, “now I am sure you will recover.”

And the next morning Don Bosco was infact convalescent.

The children's great love for their devoted benefactor showed itself in the heroic vows and promises which they offered for his recovery, many of them so severe that Don Bosco had to interpose his authority to lighten some of the self-imposed penances, and forbid the accomplishment of others.

This illness so reduced the poor priest, already so much exhausted, that he was forced to take three months to recuperate.

This time was spent in his native place, Murialdo de Castelnuovo, not far from Turin, where his family owned a small property called Les Becchi.

When his strength began to return, nothing could keep him from his children, and October found him once more in his beloved Valdoco.

Having no longer the use of the little apartment formerly allowed him by the Marquise Barolo, he determined, in order to save time, to take up his abode at the Oratory, and for this object rented from Pinardi some small rooms quite near the chapel. Then needing some one to take charge of his household affairs, he took his mother to live with him.

Don Bosco preceded his mother in this work, but later she seemed in a measure to take precedence of her son, especially when he was ordained priest. Margaret Bosco venerated her son as much as she loved him, and instinctively understood the greatness of the work to which he devoted himself. She was a large-hearted, courageous woman, and relinquished without a moment's hesitation the home of her happy married life and the peaceful seclusion of Becchi, to share the labors of her son and devote herself to his adopted family.

On the 3d of November, 1846, the mother and son left Les Becchi on foot, with walking-sticks in their hands, one carrying a breviary under his arm, the other bearing a large basket of provisions. They had in their pockets all the money they possessed, and it did not weigh heavily. A short time before reaching their destination, while passing through Rondò, they met the Abbé Vola, who more than once had lent a helping hand to Don Bosco in the night-schools and in teaching the Catechism to the children.

“How tired you seem, my good friend! Where are you going?”

“My mother and I are going to establish ourselves at the Oratory.”

“But you have neither position nor resources that I know of; how are you going to manage?”

“I know not, but Providence will provide.”

Touched by so much faith and courage, the good Abbé handed his watch to Don Bosco, saying, “I have only my watch, but I wish you would take it as a foundation stone.”

The next morning the watch was sold, for there was great need of even the simplest articles of furniture in this new household.

But there were other urgent expenditures. There was the rent, and numbers of children who had necessarily to be assisted. Some were out of employment, and would have starved but for the good bowl of soup given them by Madame Margaret Bosco; others were so miserably clad they had to be supplied with sufficient clothing to at least cover them.

Don Bosco then sold a small vineyard and a few acres of land, which comprised all his possessions. The mother disposed of her wedding presents. She had jealously preserved the beautiful linen and a few jewels received at her marriage, and valued them for their tender associations; but she unhesitatingly sold most of them, retaining a few to adorn the Blessed Virgin's altar.

Margaret Bosco soon attracted to her assistance several holy women, among them the excellent mother of the illustrious Archbishop of Turin. It is impossible to describe the devotedness of these indefatigable aids, whom the humblest and most tedious labor never wearied when there was question of the children.

In the beginning of the year 1847, Don Bosco, thus installed in the Oratory, set about improving the work, by giving it a more definite form, and by introducing more regularity in its minor details.

At this time he framed a Rule, a perfect model of its kind, which has since been, adopted by many other schools besides the Salésian.

He instituted officers, selected from among the best, most intelligent, and above all the most pious of the children. Each officer had his particular duty as well as his share of supervision and responsibility, and great care was taken to train them, that they in their turn might train others.

The conduct to be observed in church, at class, and at recreation was minutely regulated; and in order to incite the children to greater piety Don Bosco established among them a Society of St. Aloysius, in which this Saint was held up as a model under all circumstances in life.

The worthy Archbishop of Turin, Monseigneur Franzoni, approved this Society; he moreover encouraged in every possible way all Don Bosco's efforts, and as a proof of his interest gave Confirmation to the children in the humble chapel of the Oratory of Valdoco.

This ceremony took place on the feast of SS. Peter and Paul, the 29th of June, 1847, and every effort was made to give it all the pomp and solemnity possible.

Flags covered all the defects in the walls of the chapel; flowers and plants, and a triumphal arch of branches erected in front of the entrance, completed the decorations. When the Bishop ascended the pulpit and attempted to remove his mitre the ceiling proved rather low, but that did not lessen the electrifying effect of the words he addressed to his young, enthusiastic audience.

These results did not suffice to satisfy the heart of the young priest who had become the tender, watchful father of his adopted family. He sighed to see many of his children, in consequence of their precarious position and the uncertainty of obtaining work, left without shelter, obliged to sleep in stables and sheds, and even in lodgings still more injurious to them. Nothing could be more fatal than the deplorable surroundings with which they were forcibly brought in contact. It is well known how impressionable youth is, and not a few children were thus lost. To obviate this evil, Don Bosco procured a hayloft in the neighborhood of the Oratory, had the floor covered with fresh straw, and with the aid of a few quilts afforded at least a temporary lodging to those children left in the streets. When the coverings failed he took bags. Those accustomed to sleep in the streets knew well how to appreciate these bags; they crept into them, and thus had linen under and over them.

This primitive dormitory rendered good service. But Don Bosco soon learned that letting furnished lodgings was not all rose-colored. While he received only the children who frequented the Oratory all went well; but one day, or rather one evening, his charity led him to offer hospitality to a troop of little vagabonds he met in the waste lands which then surrounded the Oratory. Hoping to do them some good, he offered to lodge them. But in the morning, when he went to give them a few words of good advice, he found the place empty, not a single coverlid remained, not even a bag: they had carried them all off.

This unlucky adventure, far from discouraging Don Bosco, only incited him to do still more. A short time after this, in the month of May, an orphan, guided no doubt by the Blessed Virgin, presented himself at Don Bosco's door. He was a mason's apprentice, who had come to Turin in search of work; the small amount of money which composed all his savings was long since expended, and he had yet found no employment.

The rain was falling in torrents this evening, and the poor child was wet from head to foot. Margaret Bosco soon made a bright fire to warm the guest whom Divine Providence had sent to her hearth. When she had given him his supper, she placed a straw pallet in the middle of the kitchen, with sheets and coverings, and on this princely bed the poor child slept more contentedly than a king. This was the first boarder at the Oratory; soon a second came, then a third; finally they increased to seven.

Then they had to stop: it was impossible to accommodate another child, so small were the lodgings occupied by Don Bosco and his mother.

They were no less crowded in the place used for the reunions of the children. They came in such numbers that on certain feast-days there assembled as many as eight hundred.

The chapel, which was much frequented by the neighbors, could not accommodate them in addition to the children, many of whom were obliged to remain during the services in the class-rooms or in the court.

There was the same difficulty at the recreations: the children were so crowded together their games became very difficult, sometimes impossible.

Some measures must be taken.

Don Bosco and the Rev. Abbé Borel, his faithful companion in all his labors, held counsel together, and decided without hesitation that the only means of obviating this difficulty was to establish a second Oratory, and the Archbishop's approval having been obtained, they set to work without delay.

They rented a convenient locality—the place where the court of Victor Emmanuel II now stands. The beautiful streets, costly dwellings, and carefully kept gardens which now adorn this quarter did not then exist. There was nothing to be seen but a few small houses, and a few scattered, ruined hovels, occupied principally by washerwomen, attracted here by the nearness of the river Po.

The place selected was doubly favorable: they could do good to the population inhabiting that quarter, besides saving many of the children a long walk to and from their homes.

The new Oratory was called The Oratory of St. Louis, in honor of the venerable Archbishop of Turin, who bears that name, and also in compliment to the Society of St. Aloysius, recently established among the young men. A great many people of the world took great interest in this foundation, and aided it with their money or labor; so that the excellent society of cooperators worked admirably even from the beginning, before it was incorporated in the rules; thus giving evident proof of its usefulness. Nearly everything necessary to furnish the chapel was donated, and the ladies embroidered with their own hands the greater part of the linen and vestments.

The Oratory of St. Louis was solemnly opened on the 8th of December, 1847. A memorable anniversary; for on the 8th of December, 1841, Don Bosco received the first child of his adopted family. On the 8th of December, 1844, he inaugurated the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales in the house of the Marquise Barolo; and three years afterward, in 1847, he said Mass for the first time at the Oratory of St. Louis.

It can be seen how far the work had progressed in that comparatively short time. Two houses existed—very poor indeed in this world's goods, but most rich in the sight of God. Eight hundred children receiving the Word of God! What a marvellous treasure! The clergy of Turin, encouraged by their worthy Archbishop, earnestly lent their cooperation to the new Oratory. Several priests, under the eminent direction of the Rev. Abbé Borel, successively assumed the duties of director and chaplain, while others assisted in teaching. This state of things continued until the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales was able to furnish priests from among its members, who definitely undertook the direction of the house.

Meanwhile Don Bosco actively occupied himself with his Oratory of St. Francis de Sales, still installed in the Pindari house and shed. His great desire was to furnish food and lodgings to a certain number of children, many of whom were beyond his influence, having no assured shelter, and being compelled to earn with difficulty their daily bread. They could not even come to the Oratory on Sunday, and his best efforts were rendered useless by their deplorable poverty.

To buy the Pinardi house was hardly possible. Eighty thousand francs was the price asked for it—a sum entirely beyond his slender resources. He had to content himself with renting successively all the rooms as they were vacated by the boarders, and he devised every means of using to the best advantage a place as insufficient as it was inconvenient.

The year 1848 was a very trying one. The people were agitated and misled by revolutionary doctrines. The children could not escape such an influence, and many of them were led away and disappeared, and others became less assiduous and docile.

Don Bosco had to be satisfied with redoubling his efforts and devotion. He well knew that nothing was more capable of attracting and keeping the young people than the care which he took to instruct them. He at once considerably enlarged the schools, and thus was able to receive in the night classes more than three hundred young men: a large number, when we consider how difficult it was to make them all study with profit.

At this time he established the custom, which has always been continued in the Salésian houses, of finishing the evening's work by giving a short instruction to the children. The simplest and also the most impressive truths were explained to them. The light of infinite love was made to shine upon their young souls, as the surest means of withdrawing them from the degrading influences of evil. This practice produced marvellous fruit. A great number of the children from that time really entered a life of perfection; many manifested sentiments of deep and solid piety, and many religious vocations were developed. By prodigious efforts Don Bosco succeeded in supplying fifteen boarders with food and lodging at the Oratory.

There were fifteen other children to whom he gave food only. These children went to their work in Turin and slept at home, but they came to the Oratory for their meals. And it may be readily imagined that Don Bosco did not fail to avail himself of these occasions to give them a few words of good advice. That a greater number might profit by this arrangement he received them by series; that is, fifteen children slept and took their meals in the house from Sunday morning till Saturday evening, then the next week fifteen others took their places.

This plan was most ingenious in the good which it effected. But it no doubt entailed an extraordinary amount of care, the burden of which fell upon Don Bosco and his mother.

While good Madame Margaret was busily at work in the kitchen, occupied with the household affairs, yet finding time also to mend the children's clothes, Don Bosco was often seen doing the heavy work of the house, drawing water, sweeping, sawing the wood, lighting the fire, shelling the peas and peeling the potatoes. He did not hesitate in case of necessity to don an apron and make the polenta himself, and on those days it was pronounced to be particularly good.

Cutting out and even sewing a pair of pantaloons were not beyond his skill, and the repairs which he sometimes made on the children's clothes made up in strength for what they lacked in artistic finish. As to the refectory, it was of the most primitive kind. Each one seated himself where and how he could: some in the court on a stone or block of wood, others on the steps of the stairs, and the bowls were emptied as if by magic.

A spring of fresh water flowed near by, furnishing a drink as healthy as it was abundant. When the repast was finished, each one washed his bowl and put it away in a safe place. As to the spoons, being very precious objects, and having no drawer in which to keep them, each one kept his in his pocket. What honest sweet happiness was enjoyed in this poor household, small court and humble rooms! After grace, Don Bosco was accustomed to say to his guests, “Good appetite,” and this innocent recommendation was invariably greeted with a great burst of laughter.

The good father possessed an inexhaustible fund of gayety and youthful spirits; no one knew better than he how to amuse and interest the children. He told a story with charming humor, mingled with remarkable delicacy and grace of expression. What was wanting to the repasts in the way of seasoning was more than made up by the hearty appetites and joyousness of the guests.

Don Bosco's table was no better supplied than the children's: bread and soup, soup and bread, this was the usual bill of fare for everybody.

More than once ecclesiastics who came to assist him were obliged to leave, not being able to endure such very primitive fare. Besides the time devoted to his dear Oratory, Don Bosco managed to give private lessons to poor young men in the city, in whom he recognized special talents or a dormant vocation.

His excellent method and inexhaustible patience soon produced most distinguished pupils. Nor did he neglect for this his visits to the prisons, the Cottolengo Hospital, and to the sick nor the confessions, etc.; and above all, he made every effort to enlarge and perfect the night-school, a work which supplied in a most special manner the needs of the time. He made the study of vocal and instrumental music a very important branch in the schools. The charming voices of some of the children and the perfection of their singing impressed the people, in whom a love of music is innate. This was an additional attraction, and the number of children in the school continued to increase. Numbers of young professors and organists were educated in these schools, and exhibited remarkable talent.

The study of music became a specialty in all the Salésian houses. As soon as a foundation was established a young organist was at once appointed, and he was generally one of the children who had shown musical ability, and who continued to perfect himself while giving lessons and playing the harmonium at the church services.

Music is a specific means of moral and intellectual culture and a great aid in all religious services. The success of the night-schools was so well appreciated, that the Municipality of Turin gave Don Bosco a prize of six thousand francs in recognition of his services, and later a prize of a thousand francs for music, to which was added an annual subsidy, which was paid until 1872.

The pastors of Turin objected to the functions of the parish, first Communion, Confirmation, etc., being performed in a private institution, and complained to the Bishop; but as he had always cordially supported Don Bosco, he now invested him with the full powers of a parish priest, and the Oratory became The parish of neglected children.

It is incomprehensible that this poor priest, so devoted to his apostolic mission, should be pursued by secret animosity. This was a point of resemblance between him and St. Francis de Sales. The numerous attempts made to assassinate Don Bosco can only be attributed to the diabolical influence which then prevailed. We shall see later in what miraculous ways he escaped the attacks of those who attempted his life.

In 1849 his trials were not lessened. The spirit of revolt still spread its evil counsels, but this was all the more reason for making greater efforts to counteract it. In that year Don Bosco founded at Turin a third Oratory. It was established in the Vanchiglia quarter, then extremely poor, and entirely without a church. This Oratory was called the Angel Guardian. Later the Church of St. Julia was built near it, by the generosity of the Marquise Julia Barolo, and it was formed into a parish, to which all this quarter now belongs.

The exigencies of the war, then being waged with Austria obliged the government to quarter the soldiers in the different seminaries, from which the students were in consequence expelled. Don Bosco readily received as many as he could accommodate, and the Oratory for a time was a sort of branch of the diocesan seminary. He lodged and fed thirty of the seminarians. Don Bosco's joy was very great at this time, for four of his children from the Oratory were invested with the soutane in October, 1849. These were the first scholastics from this Institution of St. Francis de Sales, which was to assume such gigantic proportions.

Since 1846 Don Bosco had rented first a part and later the whole of Pinardi's house. In the beginning of the year 1851 he became most unexpectedly its proprietor.

Pinardi had always said that he would never part with his real estate for less than the exorbitant sum of eighty thousand francs. One day accosting Don Bosco in a tone of half jest, he said,

“Well, Don Bosco does not care to buy my house?”

“Don Bosco will buy it when Mr. Pinardi will give it to him for a reasonable price.”

“I ask eighty thousand.”

“Then let us say no more about it.”

“What do you offer then?”

“This building is valued at twenty-six or twenty-eight thousand francs: I will give you thirty for it.”

“Will you add five hundred as pin-money for my wife?”

“I will make that present.”

“You will pay the money down?”

“I will pay the money down.”

“In one payment, and in fifteen days?”

"As you wish."

“A hundred thousand francs forfeiture?”

“Well, a forfeiture of a hundred thousand francs.”

They shook hands, and the bargain, which had hardly taken five minutes, was concluded. As usual, Don Bosco had not the first cent of this sum; but there was question of the welfare of his children, so he had absolute confidence. Scarcely had Pinardi taken his departure when the Abbé Cafasso entered, bringing ten thousand francs—a generous gift from the Countess Casazza Ricardi.

The next morning a Rosminian Father came to the Oratory to consult Don Bosco about investing the sum of twenty thousand, which had been entrusted to his care. Here was a splendid opportunity. The banker Cotta added three thousand francs, and this large amount was thus secured.

The Pinardi house was bought and paid for February 19th, 1857, and Don Bosco at once set about building a church in honor of St. Francis de Sales. The one he had improvised was in a basement and consequently damp; besides which, there was so little ventilation, that often during the services the children became faint, and almost smothered for want of air.

The plan was drawn by the ingenious Blachier, and the foundation was begun at once. There was the usual absence of resources, and the usual visible intervention of Divine Providence.

An unexpected subsidy from Victor Emmanuel, numerous offerings, and finally a lottery, furnished the necessary funds.

On the 20th of January, 1852, the Church of St. Francis de Sales was solemnly consecrated. The members of the Oratory then recalled certain certain words of Don Bosco, which had passed unnoticed at the time, but with the realization of which they were now impressed.

In 1846, when they lowered the ground under the shed to transform it into a chapel, the children during recreation amused themselves by climbing on the mounds of earth which had been dug out.

One Sunday Don Bosco climbed one of the mounds with them, and made them sing several times to a particular air the following stanza:

Praised

be forever

The names of Jesus and Mary;

Forever praised be

The name of Jesus incarnate.

Then he said, “My children, some day, on this very spot where we now stand, the altar of a beautiful church will be raised, and you will come and kneel here to receive Holy Communion, and sing the praises of God.”

Five years afterward the Church of St. Francis de Sales covered this site, and the altar occupied the exact spot indicated by Don Bosco.

Having built a temple to God, Don Bosco turned his attention to a house for his children. It was necessary to give them a permanent home in order to shelter them from the temptations of the street.

He went at once to work, and large buildings rose in succession around the chapel. But this Oratory of St. Francis de Sales, which was to be the asylum of so many innocent souls, thirsting for perfection and even for sanctity, was not achieved without enduring even severe material trials.

First, there was, on the 26th of April, 1852, a terrible explosion of a powder-mill situated about five hundred yards from the Oratory, which might have levelled it to the ground; stones weighing from two to three hundred pounds were thrown into the air, and enormous burning beams fell in the court. Many walls were cracked by the concussion, and it was astonishing that the church, which had only just been finished, should have remained standing. The damage was repaired, and as soon as the church was consecrated, a large detached building, which was really indispensable, was begun.

This building was nearly finished, the beams of the roof were in place, and nothing was wanting but the tiles, when suddenly the rain came down in torrents. During the night between the 2d and 3d of December, the walls, loosened by the rain, fell with a frightful crash. Here, as at the time of the powder explosion, none of the household was injured.

The next morning the Inspector of Buildings sent an architect to examine the place. He noticed a large column, which, though out of plumb, yet supported a small house.

“Was this house occupied last night?” he asked.

“I slept there with thirty of the children.”

“Well, Monsieur l'Abbé, you may thank Our Lady: this pillar stands contrary to all the laws of equilibrium, and it is a miracle that you were not all crushed to death.”

The next year they were able to resume work on this building and complete it.

In 1860, when the Oratory was more severely menaced than ever, Don Bosco did not hesitate to purchase a large house, to which he added a story, thus doubling the accommodations for his orphans. Other buildings were added in 1862 and 1863. If the architecture of the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales of Valdoco as it now stands is somewhat irregular, it at least substantially realizes that famous plan, the description alone of which caused Don Bosco at one time to be considered insane. It can now accommodate a thousand people, besides the day pupils. It contains large workshops, where the children learn the different trades of carpenter, blacksmith, locksmith, tailor, shoemaker, baker, and bookbinder.

The printing establishment is very handsome, and beautifully fitted up. It has already furnished more than two hundred moral and educational works, as well as works of piety. A type-foundry, a shop for the manufacture of glazed paper, and another for photography and photo-engraving, complete the important trade of bookmaking. Finally, there is a large store, containing every variety of objects.

In 1865 Don Bosco laid the foundation-stone of a church dedicated to Our Lady Help of Christians, close by the Oratory.

This magnificent edifice was completed in 1868, and attracts great numbers of the faithful.

The Salésian work soon spread in a most astonishing manner. The advantages of these popular institutions, destined for the reception of poor neglected children, were so evident, that several other cities begged for Oratories like those of Turin.

Foundations of this kind were established at first in Italy, then in France, in Spain, and even in America.

There [were] in Italy, besides the three Oratories of Turin, and various smaller establishments, the Oratory and Hospital of St. Bénigne; the Collegiate Seminary of St. Charles, at Borgo San Martino; the College of St. Philip de Néri, at Lanzo-Torinese; that of the Immaculate Conception, at Valsalice, near Turin; of St. John the Baptist, at Varazze; of Our Lady of the Angels, at Alassio; the Manfredini House, at Este; the Hospital of St. Vincent de Paul, at San Pier d'Arena; the St. Paul Schools at La Spezia; the Oratory of the Cross, at Lucca; the Collegiate seminary of the Immaculate Conception, at Magliano Sabino; the establishment of St. Basile, at Randazzo; and of Bordighierra, the Parish and Hospital of the Sacred Heart at Rome.

There [were] four houses in France. The first one was established at Nice in 1875, and bears the name of the Patronage of St. Peter. Then two farm-houses— that of St. Joseph, for boys, at Navarre, near La Crau d'Hyères; and St. Isidore, for girls, at St. Cyr, in the Var.

In 1878 Don Bosco founded at Marseilles the Oratory of St. Leo, which has already received more than three hundred children.

A house was opened in Spain, at Utrera, near Séville, in 1881, and two others in 1882. These extraordinary fruits not satisfying the great charity of his apostolic heart, Don Bosco undertook to extend the work of the Catholic missions to South America.

Our Lord Jesus Christ was the first missionary sent by His Heavenly Father, and all His disciples have endeavored to continue the great mission of the redemption of the world confided to His Apostles.

Don Bosco resolved to carry the light of the Gospel to the wild, savage tribes of Patagonia.

All the missionaries who had attempted to penetrate into these distant countries had been killed, and, tradition adds, eaten. Such is said to have been the fate of the numerous Jesuit Fathers who courageously went to this inhospitable country, never to be seen again.

Every effort was vainly made to dissuade Don Bosco from such an undertaking, but, fortified by the encouragement and blessing of His Holiness Pius IX, he sent forth his missionaries.

On November 11, 1875, the first Salésian priests set sail, under the guidance of Don Cagliero, and landed at Buenos Ayres on the 14th of December.

The great gentleness and exquisite sweetness of St. Francis de Sales again triumphed over savage barbarism.

The missionaries established themselves on the confines of Patagonia, and immediately founded there a church and school.

They began by attracting to themselves the children, then a few savages, and in this way secured their first neophytes.

When it was thought advisable, they attempted an expedition into the interior of the country. They went by sea; but a violent storm overtook the ship, and, after having been tossed about for thirteen days on a stormy sea, the unfortunate missionaries found themselves just where they had started from—at the entrance of the harbor of Buenos Ayres, to which they were obliged to return.

Repulsed by the sea, they set out by land. I will not enumerate the stirring adventures of this expedition, accomplished in the midst of so many dangers. But success crowned their generous efforts. To the Salésian priests is due the honor of having planted the cross in these savage countries.

Great numbers were baptized, churches and schools were built, as well as houses for the reception of children. The glad tidings were proclaimed that the great command, Ite et docete omnes gentes (“Go, preach to all nations”), was fulfilled.

The Salésian missions of South America are not confined to Patagonia. Missions, and foundations have been established also in the Argentine Republic, Paraguay, La Plata, Uruguay, Las Pampas, and others are soon to be founded in Brazil.

The following are the names of the principal houses in the order in which they were established:

College of St. Nicholas, of Los Arroyos.

Hospital of Mercy, at Buenos Ayes.

St. Charles in Almagro, at Buenos Ayres.

Parish of Carmen, in Patagonia.

Parish of Mercy, at Viedma, in Patagonia.

Villa Colon, near Montevideo.

Charity College, at Montevideo.

Oratory of St. Vincent de Paul, in the parish of Our Lady of Peace.

Las Piedras, in the parish of St. Isidore, near Montevideo.

Paysandù, the parish of Our Lady of the Rosary.

There are besides, in Patagonia, several other stations regularly attended at stated intervals.

To sum up in large numbers:

More than a hundred thousand children have been received in the Salésian houses in Italy, France, Spain, and

in South America; besides furnishing to the Church a formidable militia of more than six thousand priests. The Word of God [was] spread in distant countries. Thousands of savages baptized.

The Sisters of Our Lady Help of Christians [taught] the little Patagonian girls.

Such is the Salésian work.

When we consider all that Don Bosco has accomplished we are struck with astonishment at the magnitude of the result obtained in so short a time. The hand of God is really visible here directing the man, who is but his instrument; but what marvels shine out in this simple and perfect course, which consists in unreserved abandonment to Divine Providence, seeking no other aid or support than the maternal assistance of the Blessed Virgin!

Let it not be imagined that Don Bosco is daring or rash in his undertakings. He never began a foundation until circumstances made it absolutely necessary; but when this was evident, he never hesitated, but went promptly to work, undeterred by want of funds, losing no time in considerations or useless preliminaries.

We must, he used to say, begin by taking the affair on our shoulders, and as we progress we soon find that the burden settles down and finds its equilibrium.

Nevertheless he always proceeded cautiously, and was humbly content at first with the most modest lodgings for his priests and children, satisfied, when he could procure it, to give them, in the beginning, bread and soup. Later, everything was much more generously supplied.

When a foundation was decided upon, he sent a few of his priests, sine sacculo et sine perâ (“without sack or scrip”), just as Our Lord told His Apostles to go.

The first time I had the pleasure of meeting a Salesian priest I could not help asking him, “Father, how do you manage to feed all these children?”

I will never forget the surprised expression of his face, and the tone in which he said, raising his hand to heaven, “Divine Providence.”

For him, charged with providing for all the wants of these children of God, there existed not a shadow of a doubt of the certain and active intervention of Divine Providence. All the priests of the Oratory of St. Francis de Sales [were] thoroughly imbued with this imperturbable faith.

Don Bosco never enlarged any of his houses unless it was absolutely necessary; that is, he always waited until there was no more room to receive the children before adding to the building. Then he set to work with great confidence, assured that the necessary funds would not be wanting, but would come in good time. The living stones, so to speak, always preceded the material ones.

Don Bosco undeniably possesses exceptional administrative ability. There is in him the making of a great minister. He keeps in mind the most minute details of each of his houses. He knows the character not only of all his priests, his clerks and his professors, but also his children, all the cooperators whom he has seen or heard of, and all the benefactors of the work. He never forgets even those he meets casually.

His memory is astonishing. It is told that at the seminary he never bought a treatise on theology. The instructions he received sufficed him, and he could repeat them word for word. Half an hour was the time allowed in the morning for dressing. He was always ready in ten minutes, and spent the rest of the time reading Rohrbacher's History, which he thus learned by heart. He could at any time, if a verse were cited to him, repeat entire pages of Dante or Virgil.

These wonderful gifts explain how, although a shepherd till his fifteenth year, he nevertheless was able to acquire such profound and solid learning.

It is incomprehensible how, with poor health, failing sight, and weak limbs, he can endure such great, incessant labor; for, besides the direction of his numerous houses, Don Bosco is always ready to listen to sufferers and console them, and the number of these is certainly very great. He receives at least two hundred letters a day, and everywhere he goes innumerable people flock to see him.

It is true he finds in his priests and in many of the laity admirable assistants, whose zeal and devotion are untiring. Then he has made it an invariable rule to attend to his immediate duties well, with great care, and without precipitation.

Although he has naturally a quick temper, he has acquired such perfect self-control that nothing can disturb his unalterable peace and serenity.

He is easy of access, and when any one is admitted to his presence he always receives him as if he were some distinguished personage who honors him by his visit. Although people sometimes take advantage of this and make him lose his valuable time, yet he never appears to think them importunate or the visit too long, and seems to have really nothing else to do but listen to them.

Never hurrying through his duties in order to accomplish a great deal, is the great secret of his success; bearing always in mind the favorite expression of one of our greatest surgeons, Nélaton, who, when he undertook a difficult and delicate operation, would say to his assistants, “Above all, let us not hurry, for we have no time to lose.”

Foolish worldlings, to whom time is money or pleasure, need to reflect upon the value this useless struggle after perishable things will one day have, when weighed in the Divine balance.

All the Salésian houses [were] regulated by a uniform system.

The professors, instructors, and the heads of the different departments [were] generally Salésians, priests, ecclesiastics, or laymen. Foreign aid is sometimes called in requisition, according to the needs of the establishment. The children learn trades and receive elementary instruction.

Those who show decided ability and special talent become students. They are taught Latin and all the studies required by the government, so that they can aspire to administrative and professional careers.

Finally, a goodly number in whom a religious vocation is decidedly manifest become priests.

Among these Don Bosco recruits the greater part of his staff, besides the priests he furnishes to the different dioceses.

Most of the parish priests of Italy, especially of Northern Italy, come from the Oratory; and the Salésian houses supply half, and sometimes three quarters, of the staff of the large seminaries of Piedmont and Lombardy.

Don Bosco's method of teaching is simple and most efficacious, and [was then] adopted by many colleges and educational houses. The classical books he has written are also perfect models. We have known young men twenty years old, scarcely knowing how to read and write, competent, after a few years' study under his system, to enter a large seminary and to become learned priests.

In regard to moral training, the children in the Salésian houses are governed by the preventive method; that is, every effort is made to prevent their committing faults, to avoid the necessity of punishing.

The priests [that were] educated in Don Bosco's schools [excelled] in the application of this method; thoroughly impregnated with the pure spirit of St. Francis de Sales, they [knew] that to love the children and win their love is the best method of governing them.

The secret of this method is comprised in the words of St. Paul: Charitas benigna est, patiens est; omnia suffert, omnia sperat, omnia sustinet (“Charity is kind, is patient; beareth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things”).

The teachers always [used to] endeavor to win the hearts of the pupils and make every effort to prevent the slightest distrust, and in their relations in which affection replaces constraint, a word, a simple glance, is sufficient reproof. Severe reprimands and punishments [were] unnecessary.

The Salésian houses [were] above all particularly distinguished for the path of Christian perfection in which the children [were] carefully trained, and the enormous good resulting therefrom. The children [made] their first Communion very young, according to the custom in the early Church. When children are intelligent and sufficiently instructed, it is not necessary to consider the age, but allow them to approach the Holy Table, that the King of Heaven may come and reign in their innocent hearts.

“Nearly all the children [used to] receive Communion every Sunday, a great many two or three times a week, and some of them every day. Frequent confession and Communion and daily Mass are the pillars which should support all education, if we wish to abolish threats and punishments.”

The children are scarcely ever left alone. All the young ecclesiastics and priests, after presiding in the workshops and at the classes, remain with the children, joining most heartily in their games. “Do what ever you like,” said St. Philip Neri, “I will be satisfied if you do not commit sin.”

Formerly Don Bosco himself joined in the games with incredible zest. He loves children devotedly, and the dear little creatures fully return his love. They never meet him without kissing his hand with an affection and tenderness touching to behold.

At one time Don Bosco could not appear in the streets of Turin without attracting a following of children.

The manner in which the different workshops are regulated is simply marvellous. The principal trades taught are those of printer, bookbinder, tailor, shoemaker, carpenter, blacksmith, as well as farming.

Poor human nature rebels against the hard law of labor; but the soul, if not neglected, may find in it a profitable means of advancement.

Often during the day, and especially in the evening after work, a few words of spiritual comfort are addressed to the children. They are reminded how manual labor was honored and glorified by Our Lord Himself, who was during his mortal life a simple workman like them. They are told of this adorable model and of his Heavenly Father, by whom He was received on His triumphant entry into heaven after the sorrows and trials of His life on earth.

The Christian workshop is a veritable abode of profound peace and unalterable happiness when the work is properly considered, and not merely endured, but joy fully accepted and sanctified. Armed with solid piety, these young men can valiantly encounter the difficulties of life, and walk unflinchingly in the right path; and such is generally the result of the Salésian teachings. A goodly number of them have attained very honorable positions. Some [had] become good merchants and noted manufacturers. Others [had] raised themselves to the highest places in the government, the public schools, the magistracy, and the army. But whether fortune smiles upon them, or whether they remain in the humblest position, their love for the house in which they were educated never alters. If it is in their power, they never fail to return every year to make a retreat; and they always retain unbounded veneration and gratitude for Don Bosco and their former masters.

But the characteristic trait of the thousands of children educated in the Salésian houses must not be forgotten. Not one of them, since the first day of the foundation, has ever been arrested or condemned by the judiciary.

It is a well-known, undeniable fact, that the Salésian Society, by its care of poor, abandoned children, renders signal service to the country. Twenty-five thousand children leave these houses every year, and the same number is received, and all these young men become good, honest citizens, men of worth and merit; thus this work contributes in a great measure to the honor and prosperity of the nation.

Applications come from all parts and all countries to Don Bosco for Salesian Institutes; but unfortunately he is unable to satisfy all the demands, for want of sufficient funds and for lack of assistants.

I now come to a subject which it is necessary to treat with great delicacy. I wish to speak of the innumerable cures and the signal favors obtained by Don Bosco, in which the direct intervention of the Blessed Virgin, under the title of “Our Lady Help of Christians,” is readily recognized.

These favors were especially manifested at the time Don Bosco commenced the beautiful church dedicated under this title. A sudden cure was obtained at the end of a novena to Our Lady Help of Christians, and soon resulted in an immense concourse of people coming from great distances, soliciting cures and graces of all kinds.

Don Bosco simply advised all of them to make a novena to Our Lady Help of Christians, and to promise an offering for her church if their prayers were granted. The offerings which came from this source—that is, from favors obtained—were so numerous and so large, that they alone almost sufficed to cover the entire expense of building this magnificent edifice.

These favors have since multiplied beyond computation, so that it is almost impossible to enumerate them.

Does it not seem evident that Our Lady Help of Christians thus wishes to testify how pleasing to her is the care taken of so many neglected children, and that the Divine Mother wishes to procure in this way the material resources necessary to sustain the Salésian work?

The amount realized from the labor of the children in the various shops is not sufficient to aid materially in the work of the Society. Most of them are young and yet unskilled in the trades they are learning, and many of them are students. It is appalling to estimate the enormous sum required to carry on this work.

A hundred thousand children, most of whom have to be fed and clothed; a hundred and thirty houses, in which the daily expenditure is very great; then the missionaries to be sent to foreign countries and supported. And, in addition to this heavy burden, His Holiness Leo XIII [had] lately entrusted to Don Bosco the finishing of the Church of the Sacred Heart, [then] being built at Castro Pretorio, on Mount Esquiline, in Rome. He has to obtain the sum necessary to finish this important edifice, to which is to be attached a Salésian institute capable of accommodating a large number of children of all nationalities.

The Salésian work having no other resource than that of voluntary contributions, Our Lady Help of Christians ceases not to manifest her power, and to bestow favors on those who remember Don Bosco's children.

Hence, if people are not prompted by motives of faith and charity to render assistance, they may contribute through interested motives, for the promise is infallible.

“Centies tantum nunc, in tempore hoc . . . et in sӕculo futuro vitam ӕternam” (Mark x. 30). “An hundred times as much now in this time . . . and in the world to come life everlasting.” Some obtain material prosperity, others, receive favors of a much higher order, graces and cures, such as a loved one rescued from the grasp of death, an invalid restored to health. . . .

Sometimes the cure is immediate, but generally it does not take place immediately, the disease following its natural

course.

Don Bosco, like the Curé of Ars, dreads notoriety. He usually says to those who apply to him for prayers, “You will come at such a time to return thanks to Our Lady Help of Christians,” or, “We will pray for you.”

To obtain a favor, Don Bosco generally advises a novena to Our Lady, composed of Three Our Fathers, Hail Marys, Glory be to the Fathers, and the Hail Holy Queen. He has a singular devotion to this last prayer, and he never fails to furnish the person with a medal of Our Lady Help of Christians. He advises some work of charity as thanksgiving for graces obtained, but leaves everybody perfectly free in this matter, and in his delicacy refrains from even suggesting one of his own houses as the object of charity, although it is especially to these establishments that Our Lady Help of Christians has shown her protection.

He has the children in all the houses pray for the benefactors, and when a particular favor is asked, these prayers never fail to reach heaven.

It would require a very large volume to contain the history of the precious graces thus obtained…

It can at least be said that those persons who have sought to obtain the protection of Divine Providence in their temporal affairs, by giving a tenth of their income to the support of these poor, abandoned children cared for in the Salésian houses, have in almost every instance realized this blessing beyond their greatest hopes or expectation.

If I thought it prudent, I could add to this sketch very many interesting facts. I could, for example, tell how, when His Holiness Pius IX took refuge at Gaeta, Don Bosco prophesied to him the events that would signalize his reign. I could also speak of the singular esteem and veneration that this great Pope had for Don Bosco, sentiments in which his successor, Leo XIII, also shares.

The following are the four principal works founded by Don Bosco:

1. The Salésian Association, with its priests, laymen, and missionaries.

2. The Institute of the Daughters of Marie Auxiliatrice.

3. The Society of Marie Auxiliatrice, for helping young men studying for the priesthood.

4. Finally, the Co-operators of St. Francis de Sales, a pious Association…

The Co-operators of St. Francis de Sales

When Don Bosco began in 1841 to gather together poor, abandoned children from the streets and lanes of Turin, Providence soon sent him assistants who associated themselves with him in this noble work.

Several priests and laymen came to his assistance in the care of the children. Some taught them catechism, and helped in the classes; others obtained for those out of place good Christian masters.

As these poor little people were generally in rags, pious ladies of rank, and of all classes in Turin, took upon themselves the task of mending their clothes and of making them new ones.

Such was the origin of the Co-operators of St. Francis de Sales. Their number [then exceeded to] eighty thousand, ten thousand of which [were] in France.

The Association did so much good, that Don Bosco, wishing to give it permanent form, framed for it, in 1858, rules, which he perfected in 1864 and 1868.

These rules were several times submitted to His Holiness Pius IX, and were finally finished and definitely adopted in 1874.

This Association of Salésian Co-operators received from Pius IX, of immortal memory, the most marked encouragement.

He had his name inscribed at the head of the list of Co-operators, and established the Association in the Third Order. He commanded the Congregation of Rites to grant to said Co-operators all the indulgences that may be gained by the Tertiaries of the most favored orders, especially the Tertiaries of St. Francis of Assisi.

The following is the brief of Pius IX, dated May 9th, 1876.