August 12, 2020: ST. CLARE OF ASSISI

August 12, 2020: ST. CLARE (OF ASSISI), VIRGIN

Rank: Double.

“How much am I obliged to my sweet Redeemer! for since, by means of his servant Francis, I have tasted the bitterness of his holy passion”

Prayer (Collect).

Give ear to us, O God our Saviour, that as we celebrate with joy the solemnity of blessed Clare, thy Virgin, so we may improve in the affection of piety. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, thy Son, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God, world without end. Amen.

The same year in which St. Dominic, before making any project with regard to his sons, founded the first establishment of the Sisters of his Order, the companion destined for him (St. Francis of Assisi) by heaven received his mission from the Crucifix in the church of St. Damian, in these words: “Go, Francis, repair my house which is falling to ruin.” The new patriarch inaugurated his work, as Dominic had done, by preparing a dwelling for his future daughters, whose sacrifice might obtain every grace for the great Order he was about to found. The house of the Poor Ladies occupied the thoughts of the seraph of Assisi, even before St. Mary of the Portiuncula, the cradle of the Friars Minor. Thus, for a second time this month, Eternal Wisdom shows us that the fruit of salvation, though it may seem to proceed from the word and from action, springs first from silent contemplation.

Clare was to Francis the help like unto himself, who begot to the Lord that multitude of heroic virgins and illustrious penitents soon reckoned by the Order in all lands, coming from the humblest condition and from the steps of the throne. In the new chivalry of Christ, Poverty, the chosen Lady of St. Francis, was to be the queen also of her whom God had given him as a rival and a daughter. Following to the utmost limits the Man-God humbled and stripped of all things for us, she nevertheless felt that she and her sisters were already queens in the kingdom of heaven: “In the little nest of poverty,” she used lovingly to say, “what jewel could the bride esteem so much as conformity with a God possessing nothing, become a little One whom the poorest of mothers wrapt in humble swathing bands and laid in a narrow crib?” And she bravely defended against the highest authorities the privilege of absolute poverty, which the great Pope Innocent III feared to grant.

This noble daughter of Assisi had justified the prophecy, whereby sixty years previously, her mother Hortulana had learnt that the child would enlighten the world; the choice of the name given her at her birth had been well inspired. “Oh! how powerful was the virgin's light,” said the sovereign Pontiff in the Bull of her Canonization; “how penetrating were her rays! She hid herself in the depth of the cloister, and her brightness transpiring filled the house of God.” (Bulla Canonizationis) From her poor solitude which she never quitted, the very name of Clare seemed to carry grace and light everywhere, and made far-off cities yield fruit to God and to her father, St. Francis.

Embracing the whole world where her virginal family was being multiplied, her motherly heart overflowed with affection for the daughters she had never seen. Let those who think that austerity embraced for God's sake dries up the soul, read these lines from her correspondence with Blessed Agnes of Bohemia. Agnes, daughter of Ottacar I, had rejected the offer of an imperial marriage to take the religious Habit, and was renewing at Prague the wonders of St. Damian's. “O my mother and my daughter,” said our Saint, “if I have not written to you as often as my soul and yours would wish, be not surprised: as your mother's heart loved you, so do I cherish you; but messengers are scarce, and the roads full of danger. As an opportunity offers to-day, I am full of gladness, and I rejoice with you in the joy of the Holy Ghost. As the first Agnes united herself to the immaculate Lamb, so it is given to you, O fortunate one, to enjoy this union (the wonder of heaven) with him, the desire of whom ravishes every soul; whose goodness is all sweetness, whose vision is beatitude, who is the light of the eternal light, the mirror without spot! Look at yourself in this mirror, O queen! O bride! unceasingly by its reflection enhance your charms; without and within adorn yourself with virtues; clothe yourself as beseems the daughter and the spouse of the supreme King. O beloved, with your eyes on this mirror, what delight it will be given you to enjoy in the divine grace! . . . Remember, however, your poor Mother, and know that for my part your blessed memory is for ever graven on my heart.”

Not only did the Franciscan family benefit by a charity which extended to all the worthy interests of this world. Assisi, delivered from the lieutenants of the excommunicated Frederick II and from the Saracen horde in his pay, understood how a holy woman is a safeguard to her earthly city. But our Lord loved especially to make the princes of holy Church and the Vicar of Christ experience the humble power, the mysterious ascendency, wherewith he had endowed his chosen one. St. Francis himself, the first of all, had in one of those critical moments known to the Saints, sought from her direction and light for his seraphic soul. From the ancients of Israel, there came to this virgin not yet thirty years old, such messages as this: “To his very dear Sister in Jesus Christ, to his mother the Lady Clare handmaid of Christ, Hugolin of Ostia, unworthy bishop and sinner. Ever since the hour when I had to deprive myself of your holy conversation, to snatch myself from that heavenly joy, such bitterness of heart causes my tears to flow, that, if I did not find at the feet of Jesus the consolation which his love never refuses, my mind would fail and my soul would melt away. Where is the glorious joy of that Easter spent in your company and that of the other handmaids of Christ? ... I knew that I was a sinner; but at the remembrance of your supereminent virtue, my misery overpowers me, and I believe myself unworthy ever to enjoy again that conversation of the Saints, unless your tears and prayers obtain pardon for my sins. I put my soul, then, into your hands; to you I intrust my mind, that you may answer for me on the day of judgment. The Lord Pope will soon be going to Assisi; Oh! that I may accompany him, and see you once more! Salute my sister Agnes (i.e. St. Clare's own sister and first daughter in God); salute all your sisters in Christ.”

The great Cardinal Hugolin, though more than eighty years of age, became soon after Gregory IX. During his fourteen years' pontificate, which was one of the most brilliant as well as most laborious of the thirteenth century, he was always soliciting Clare's interest in the perils of the Church, and the immense cares which threatened to crush his weakness. For, says the contemporaneous historian of our Saint: “He knew very well what love can do, and that virgins have free access to the sacred court: for what could the King of heaven refuse to those, to whom he has given himself?”

At length her exile, which had been prolonged twenty-seven years after the death of Francis, was about to close. Her daughters beheld wings of fire over her head and covering her shoulders, indicating that she, too, had reached seraphic perfection. On hearing that a loss which so concerned the whole Church was imminent, the Pope, Innocent IV, came from Perugia with the Cardinals of his suite. He imposed a last trial on the Saint's humility, by commanding her to bless, in his presence, the bread which had been presented for the blessing of the sovereign Pontiff; heaven approved the invitation of the Pontiff and the obedience of the Saint, for no sooner had the virgin blessed the loaves than each was found to be marked with a cross.

A prediction that Clare was not to die without receiving a visit from the Lord surrounded by his disciples was now fulfilled. The Vicar of Jesus Christ presided at the solemn funeral rites paid by Assisi to her who was its second glory before God and men. When they were beginning the usual chants for the dead, Innocent would have had them substitute the Office for holy Virgins; but on being advised that such a canonization, before the body was interred, would be considered premature, the Pontiff allowed them to continue the accustomed chants. The insertion, however, of the Virgin's name in the catalogue of the Saints was only deferred for two years.

The following lines are consecrated by the Church to her memory:

The noble virgin Clare was born at Assisi, in Umbria. Following the example of St. Francis, her fellow-citizen, she distributed all her goods in alms to the poor, and, fleeing from the noise of the world, she retired to a country church, where blessed Francis cut off her hair. Her relations attempted to bring her back to the world, but she bravely resisted all their endeavours; and then St. Francis took her to the church of St. Damian. Here our Lord gave her several companions, so that she founded a convent of consecrated virgins, and her reluctance being overcome by the earnest desire of her holy father, she undertook its government. For forty-two years she ruled her monastery with wonderful care and prudence, in the fear of God and the full observance of the Rule. Her own life was a lesson and an example to others, showing all how to live aright.

She subdued her body in order to grow strong in spirit. Her bed was the bare ground, or, at times, a few twigs, and for a pillow she used a piece of hard wood. Her dress consisted of a single tunic and a mantle of poor coarse stuff; and she often wore a rough hair-shirt next to her skin. So great was her abstinence, that for a long time she took absolutely no bodily nourishment for three days of the week, and on the remaining days restricted herself to so small a quantity of food, that the other religious wondered how she was able to live. Before her health gave way, it was her custom to keep two Lents in the year, fasting on bread and water. Moreover, she devoted herself to watching and prayer, and in these exercises especially she would spend whole days and nights. She suffered from frequent and long illnesses; but when she was unable to leave her bed in order to work, she would make her sisters raise and prop her up in a sitting position, so that she could work with her hands, and thus not be idle even in sickness. She had a very great love of poverty, never deviating from it on account of any necessity, and she firmly refused the possessions offered by Gregory IX for the support of the sisters.

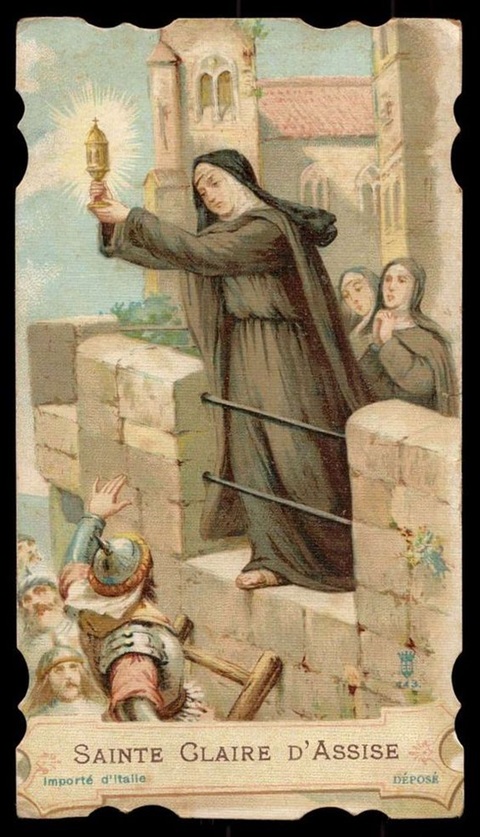

The greatness of her sanctity was manifested by many different miracles. She restored the power of speech to one of the sisters of her monastery, to another the power of hearing. She healed one of a fever, one of dropsy, one of an ulcer, and many others of various maladies. She cured of insanity a brother of the Order of Friars Minor. Once when all the oil in the monastery was spent, Clare took a vessel and washed it, and it was found filled with oil by the loving kindness of God. She multiplied half a loaf so that it sufficed for fifty sisters. When the Saracens attacked the town of Assisi and attempted to break into Clare's monastery, she, though sick at the time, had herself carried to the gate, and also the vessel which contained the most Holy Eucharist, and there she prayed, saying: “O Lord, deliver not unto beasts the souls of them that praise thee; but preserve thy handmaids whom Thou hast redeemed with thy precious Blood.” Whereupon a voice was heard, which said: “I will always preserve you.” Some of the Saracens took to flight, others who had already scaled the walls were struck blind and fell down headlong. At length, when the virgin Clare came to die, she was visited by a white-robed multitude of blessed virgins, amongst whom was one nobler and more resplendent than the rest. Having received the Holy Eucharist and a Plenary Indulgence from Innocent IV, she gave up her soul to God on the day before the Ides of August. After her death she became celebrated by numbers of miracles, and Alexander IV enrolled her among the holy virgins.

Another account of St. Clare.

St. Clare was daughter to Phavorino Sciffo, a noble knight who had distinguished himself in the wars, and his virtuous spouse called Hortulana. These illustrious personages, who held the first rank at Assisium for their birth and riches, were still more eminent for their extraordinary piety. They had three daughters, Clare, Agnes, and Beatrice. St. Clare was born in 1193, at Assisium, a city in Italy, built on a stony mountain called Assi; from her infancy she was extremely charitable and devout. It was her custom to count her task of Paters and Aves by a certain number of little stones in her lap, in imitation of some ancient anchorets in the East. Her parents began to talk to her very early of marriage, which gave her great affliction; for it was her most ardent desire to have no other spouse but Jesus Christ. Hearing the great reputation of St. Francis, who set an example of perfection to the whole city, she found means to be conducted to him by a pious matron, and begged his instruction and advice. He spoke to her on the contempt of the world, the shortness of life, and the love of God and heavenly things in such a manner as warmed her tender breast; and, upon the spot, she formed a resolution of renouncing the world. St. Francis appointed Palm Sunday for the day on which she should come to him. On that day Clare, dressed in her most sumptuous apparel, went with her mother and family to the divine office; but when all the rest went up to the altar to receive a palm-branch, bashfulness and modesty kept her in her place; which the bishop seeing, he went from the altar down to her and gave her the palm. She attended the procession; but the evening following it, being the 18th of March, 1212, she made her escape from home, accompanied with another devout young woman, and went a mile out of the town to the Portiuncula, where St. Francis lived with his little community. He and his religious brethren met her at the door of their church of our Lady with lighted tapers in their hands, singing the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus. Before the altar of the Blessed Virgin she put off her fine clothes, and St. Francis cut off her hair, and gave her his penitential habit, which was no other than a piece of sackcloth, tied about her with a cord. The holy father not having yet any nunnery of his own, placed her for the present in the Benedictin nunnery of St. Paul, where she was affectionately received, being then eighteen years of age. The Poor Clares date from this epoch the foundation of their Order.

No sooner was this action of the holy virgin made public, but the world conspired unanimously to condemn it, and her friends and relations came in a body to draw her out of her retreat. Clare resisted their violence, and held the altar so fast as to pull the holy cloths half off it when they endeavoured to drag her away; and, uncovering her head to show her hair cut, she said that Christ had called her to his service, and that she would have no other spouse of her soul; and that the more they should continue to persecute her, the more God would strengthen her to resist and overcome them. They reproached her that by embracing so poor and mean a life she disgraced her family; but she bore their insults, and God triumphed in her. St. Francis soon after removed her to another nunnery, that of St. Angelo of Panso, near Assisium, which was also of St. Bennet's Order. There her sister Agnes joined her in her undertaking; which drew on them both a fresh persecution, and twelve men abused Agnes both with words and blows, and dragged her on the ground to the door, whilst she cried out, “Help me, sister; permit me not to be separated from our Lord Jesus Christ, and your loving company.” Her constancy proved at last victorious, and St. Francis gave her also the habit, though she was only fourteen years of age. He placed them in a new mean house, contiguous to the Church of St. Damian, situated on the skirts of the city Assisium, and appointed Clare the superior. She was soon after joined by her mother, Hortulana, and several ladies of her kindred, and others, to the number of sixteen, among whom three were of the illustrious family of the Ubaldini, in Florence. Many noble princesses held for truer greatness the sackcloth and poverty of St. Clare than the estates, delights, and riches which they possessed, seeing they left them all to become humble disciples of so holy and admirable a mistress. St. Clare founded, within a few years, monasteries at Perugia, Arezzo, Padua, that of SS. Cosmas and Damian in Rome; at Venice, Mantua, Bologna, Spoletto, Milan, Sienna, Pisa, &c, also at many principal towns in Germany. Agnes, daughter to the King of Bohemia, founded a nunnery of her Order in Prague, in which herself took the habit.

St. Clare and her community practised austerities which till then had scarce ever been known among the tender sex. They wore neither stockings, shoes, sandals, nor any other covering on their feet; they lay on the ground, observed a perpetual abstinence, and never spoke but when they were obliged to it by the indispensable duties of necessity and charity. The foundress, in her rule, extremely recommends this holy silence as the means to retrench innumerable sins of the tongue, and to preserve the mind always recollected in God, and free from the dissipation of the world, which without this guard penetrates the walls of cloisters. Not content with the four Lents, and the other general mortifications of her rule, she always wore next her skin a rough shift of horsehair or of hogs' bristles cut short; she fasted church vigils and all Lent on bread and water; and from the 11th of November to Christmas-day, and during these times, on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, ate nothing at all. She sometimes strewed the ground on which she lay with twigs, having a block for her bolster. Her disciplines, watchings, and other austerities were incredible, especially in a person of so tender a constitution. Being reduced to great weakness and to a very sickly state of health, St. Francis and the Bishop of Assisium obliged her to lie upon a little chaff, and never pass one day with out taking at least some bread for nourishment. Under her greatest corporal austerities her countenance was always mild and cheerful, demonstrating that true love makes penance sweet and easy. Her esteem of holy poverty was most admirable. She looked upon it as the retrenchment of the most dangerous objects of the passions and self-love, and as the great shool of patience and mortification, by the perpetual inconveniences and sufferings which it lays persons under, and which the spirit of Christ crucified teaches us to bear with patience and joy. It carries along with it the perfect disengagement of the heart from the world, in which the essence of true devotion consists. The saint considered in what degree Christ, having for our sakes relinquished the riches of his glory, practised holy poverty in his birth, without house or other temporal conveniency; and, during his holy ministry, without a place to lay his head in, and living on voluntary contributions; but, above all, his poverty, nakedness, and humiliation on the cross, and at his sacred death, were deeply imprinted on her mind, and she ardently sought to bear for his sake some resemblance of that state which he had assumed for us to apply a proper remedy to our spiritual wounds, and heal the corruption of our nature.

St. Francis instituted that his Order should never possess any rents even in common, subsisting on daily contributions. St. Clare possessed this spirit in such perfection, that when her large fortune fell to her, by the death of her father, after her profession, she gave the whole to the poor, without reserving one single farthing for the monastery. Pope Gregory IX desired to mitigate this part of her rule, and offered to settle a yearly revenue on her monastery of St. Damian's; but she, in the most pressing manner, persuaded him by many reasons, in which her love of evangelical poverty made her eloquent, to leave her Order in its first rigorous establishment. Whilst others asked riches, Clare presented again her most humble request to Pope Innocent IV that he would confirm to her Order the singular privilege of holy poverty, which he did, in 1251, by a bull written with his own hand, which he watered at the same time with tears of devotion. So dear was poverty to St. Clare, chiefly for her great love of humility. Though superior, she would never allow herself any privilege or distinction. It was her highest ambition to be the servant of servants, always beneath all, washing the feet of the lay-sisters, and kissing them when they returned from begging, serving at table, attending the sick, and removing the most loathsome filth. When she prayed for the sick, she sent them to her other sisters, that their miraculous recovery might not be imputed to her prayers or merits. She was so true a daughter of obedience, that she had always as it were, wings to fly wherever St. Francis directed her, and was always ready to execute anything, or to put her shoulders under any burden that was enjoined her; she was so crucified, to her own will, as to seem entirely divested of it. This she expressed to her holy father as follows:— “Dispose of me as you please; I am yours by having consecrated my will to God. It is no longer my own.”

Prayer was her spiritual comfort and strength, and she seemed scarce ever to interrupt that holy exercise. She often prostrated herself on the ground, kissed it, and watered it with many tears. Whilst her sisters took their rest, she watched long in prayer, and was always the first that rose, rung the bell in the choir, and lighted the candles. She came from prayer with her face so bright and inflamed (like that of Moses descending from conversing with God), that it often dazzled the eyes of those that beheld her; and every one perceived, by her words, that she came from her devotions; for she spoke with such a spirit and fervour as enkindled a flame in all who did but hear her voice, and diffused into their souls a great esteem of heavenly things. She communicated very often, and had a wonderful devotion towards the blessed Sacrament. Even when she was sick in bed, she spun with her own hands fine linen for corporals, and for the service of the altar, which she distributed through all the churches of Assisium. In prayer she was often so absorbed in divine love as to forget herself and her corporal necessities. She, on many occasions, experienced the all-powerful force and efficacy of her holy prayer. A remarkable instance is mentioned in her life. The impious Emperor Frederic II cruelly ravaged the Valley of Spolletto, because it was the patrimony of the Holy See. He had in his army many Saracens and other barbarous infidels, and left in that country a colony of twenty thousand of these enemies of the church in a place still called Noura des Moros. These banditti came once in a great body to plunder Assisium, and as St. Damian's convent stood without the walls, they first assaulted it. Whilst they were busy in scaling the walls, St. Clare, though very sick, caused herself to be carried and seated at the gate of the monastery, and the blessed Sacrament to be placed there in a pix in the very sight of the enemies, and, prostrating herself before it, prayed with many tears, saying to her beloved spouse, “Is it possible, my God, that thou shouldst have here assembled these thy servants, and nurtured them up in thy holy love, that they should now fall into the power of these infidel Moors! Preserve them, O my God, and me in their holy company.” At the end of her prayer, she seemed to hear a sweet voice, which said, “I will always protect you.” A sudden terror, at the same time, seized the assailants, and they all fled with such precipitation, that several were hurt without being wounded by any enemy. Another time, Vitalis Aversa, a great general of the same emperor, a cruel and proud man, laid siege to Assisium for many days. St. Clare said to her nuns, that they who had received corporal necessaries from that city, owed to it all assistance in their power in its extreme necessity. She, therefore, bid them cover their heads with ashes, and in this most suppliant posture beg of Christ the deliverance of the town. They continued pressing their request with many tears a whole day and night, till powerful succours arriving, the besiegers silently raised the siege, and retired without noise, and their general was soon after slain.

St. Francis was affected with the most singular and tender devotion towards the mysteries of Christ's nativity and sacred passion. He used to assemble incredible numbers of the people to pass the whole Christmas night in the church in fervent prayer; and, at midnight, once preached with such fervour and tenderness, that he was not able to pronounce the name Jesus, but called him the little child of Bethlehem; and, in repeating these words, always melted away with tender love. St. Clare inherited this same devotion and tenderness to this holy mystery, and received many special favours from God in her prayers on that festival. As to the passion of Christ, St. Francis called it his perpetual book, and said he never desired to open any other but the history of it in the gospels, though he were to live to the world's end. The like were the sentiments of St. Clare towards it; nor could she call to mind this adorable mystery without streams of tears, and the warmest emotions of tender love. In sickness particularly it was her constant entertainment. She was afflicted with continual diseases and pains for eight-and-twenty years, yet was always joyful, allowing herself no other indulgence than a little straw to lie on. Reginald, Cardinal of Ostia, afterwards Pope Alexander IV, both visited her and wrote to her in the most humble manner. Pope Innocent IV paid her a visit a little before her death, going from Perugia to Assisium on purpose, and conferring with her a long time on spiritual matters with wonderful comfort.

St. Clare bore her sickness and great pains without so much as speaking of them, and when Brother Reginald exhorted her to patience, she said, “How much am I obliged to my sweet Redeemer! for since, by means of his servant Francis, I have tasted the bitterness of his holy passion, I have never in my whole life found any pain or sickness that could afflict me. There is nothing insupportable to a heart that loveth God; and to him that loveth not, everything is insupportable.” Agnes, seeing her dear sister and spiritual mother draw near her end, besought her, with great affection and many tears, that she would take her along with her, and not leave her here on earth, seeing they had been such faithful companions, and so united in the same spirit and desire of serving our Lord. The holy virgin comforted her, telling her it was the will of God she should not at present go along with her; but bade her be assured she should shortly come to her, and so it happened. St. Clare, seeing all her spiritual children weep, comforted them, and tenderly exhorted them to be constant lovers and faithful observers of holy poverty, and gave them her blessing, calling herself the little plant of her holy father St. Francis. The passion of Christ, at her request, was read to her in her agony, and she sweetly expired amidst the prayers and tears of her community, on the 11th of August, 1253, in the forty-second year after her religious profession, and the sixtieth of her age. She was buried on the day following, on which the church keeps her festival. Pope Innocent IV came again from Perugia, and assisted in person with the sacred college at her funeral. Alexander IV canonized her at Anagnia, in 1255. Her body was first buried at St. Damian's; but the pope ordered a new monastery to be built for her nuns at the Church of St. George within the walls, which was finished in 1260, when her relics were translated thither with great pomp. A new church was built here afterwards, which bears her name; in which, in 1265, Pope Clement V consecrated the high altar under her name, and her body lies under it. The body of St. Francis had lain in this Church of St. George four years, when, in 1230, it was removed to that erected in his honour, in which it still remains. Camden remarks that the family name Sinclair among us is derived from St. Clare.

The example of this tender virgin, who renounced all the softness, superfluity, and vanity of her education, and engaged and persevered in a life of so much severity, is a reproach of our sloth and sensuality. Such extraordinary rigours are not required of us; but a constant practice of self-denial is indispensably enjoined us by the sacred rule of the gospel, which we all have most solemnly professed. Our backwardness in complying with this duty is owing to our lukewarmness, which creates in everything imaginary difficulties, and magnifies shadows. St. Clare, notwithstanding her continual extraordinary austerities, the grievous persecutions she had suffered, and the pains of a sharp and tedious distemper with which she was afflicted, was surprised when she lay on her death-bed, to hear any one speak of her patience, saying, that from the time she had first given her heart to God, she had never met with anything to suffer, or to exercise her patience. This was the effect of her ardent charity. Let none embrace her holy institute without a fervour which inspires a cheerful eagerness to comply, in the most perfect manner, with all its rules and exercises; and without seriously studying to obtain, and daily improve, in their souls, her eminent spirit of poverty, humility, obedience, love of silence, mortification, recollection, prayer, and divine love. In this consists their sanctification; in this they will find all present and future blessings and happiness.

Taken from: The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal

Saints, Vol. II.

The Liturgical Year - Time after Pentecost, Vol. IV, Dublin, Edition 1901; and

The Divine Office for the use of the Laity, Volume II, 1806.

St. Clare, pray for us.