February 8, 2018: ST. JOHN OF MATHA

February 8, 2018: ST. JOHN OF MATHA, CONFESSOR

Rank: Double

[Founder of the Order of the Trinitarians]

Thy charity was formed on the model of that which is in the heart of God, who loves our soul, yet disdains not to provide for the wants of our body. Seeing so many souls in danger of apostacy, thou didst run to their aid, and men were taught to love a religion which can produce heroes of charity like thee.

Prayer (Collect).

O God, who, by holy John, wast pleased with thy heavenly directions to institute the order of the most holy Trinity, for the redeeming of captives out of the hands of the Saracens: grant, we beseech thee, that, by his merits, we may be delivered from all captivity, both of body and mind, by the assistance of thy holy grace. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, thy Son, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God, world without end. Amen.

We were celebrating, not many days ago, the memory of Peter Nolasco, who was inspired, by the Holy Mother of God, to found an Order for the ransoming of Christian captives from the infidels: to-day, we have to honour the generous Saint, to whom this sublime work was first revealed. He established, under the name of the Most Holy Trinity, a body of religious men, who bound themselves by vow to devote their energies, their privations, their liberty, nay, their very life, to the service of the poor slaves who were groaning under the Saracen yoke. The Order of the Trinitarians, and the Order of Mercy, though distinct, have the same end in view, and the result of their labours, during the six hundred years of their existence, has been the restoring to liberty and preserving from apostacy upwards of a million slaves. John of Matha, assisted by his faithful cooperator, Felix of Valois, (whose feast we shall keep at the close of the Year,) established the centre of his grand work at Meaux, in France. We are preparing for Lent, when one of our great duties will have to be that of charity towards our suffering brethren: what finer model could we have than John of Matha, and his whole Order, which was called into existence for no other object than that of delivering from the horrors of slavery brethren who were utter strangers to their deliverers, but were in suffering and in bondage. Can we imagine any almsgiving, let it be ever so generous, which can bear comparison with this devotedness of men, who bind themselves by their Rule, not only to traverse every Christian land begging alms for the ransom of slaves, but to change places with the poor captives, if their liberty cannot be otherwise obtained? Is it not, as far as human weakness permits, following to the very letter, the example of the Son of God himself, who came down from heaven that he might be our ransom and Redeemer? We repeat it,—with such models as these before us, we shall feel ourselves urged to follow the injunction we are shortly to receive from the Church, of exercising works of mercy towards our fellow creatures, as being one of the essential elements of our Lenten penance.

But it is time we should listen to the account given us by the Liturgy of the virtues of this apostolic man, who has endeared himself, both to the Church and mankind, by his heroism of charity.

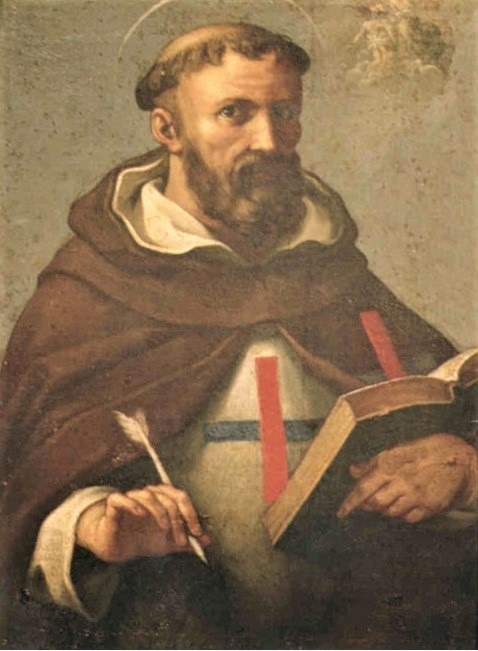

John of Matha, the Institutor of the Order of the Most Holy Trinity for the Ransom of captives, was born at Faucon, in Provence, of parents conspicuous for their nobility and virtue. He went through his studies first at Aix, and afterwards at Paris, where, after having completed his theological course, he received the degree of Doctor. His eminent learning and virtues induced the Bishop of Paris to promote him, in spite of his humble resistance, to the holy order of priesthood, that, during his sojourn in that city, he might be a bright example to young students by his talents and piety. Whilst celebrating his first mass in the Bishop's chapel, in the presence of the Prelate and several assistants, he was honoured by a signal favour from heaven. There appeared to him an Angel clad in a white and brilliant robe; he had on his breast a red and blue cross, and his arms were stretched out, crossed one above the other, over two captives, one a Christian, the other a Moor. Falling into an ecstacy at this sight, the man of God at once understood that he was called to ransom captives from the infidels.

But, that he might the more prudently carry out so important an undertaking, he withdrew into a solitude. There, by divine appointment, he met with Felix of Valois, who had been living many years in that same desert. They agreed to live together, and for three years did John devote himself to prayer, and contemplation, and the practice of every virtue. It happened, that as they were one day seated near a fountain, conferring with each other on holy things, a stag came towards them, bearing a red and blue cross between his antlers. John, perceiving that Felix was surprised by so strange an occurrence, told him of the vision he had had in his first mass. They gave themselves more fervently than ever to prayer, and having been thrice admonished in sleep, they resolved to set out for Rome, there to obtain permission from the Sovereign Pontiff to found an Order for the ransom of captives. Innocent the Third, who had shortly before been elected Pope, received them kindly, and whilst deliberating upon what they proposed, it happened, that as he was celebrating mass in the Lateran Church, on the second feast of St. Agnes, there appeared to him, during the elevation of the sacred Host, an Angel robed in white, bearing a two-coloured cross, and in the attitude of one that was rescuing captives. Whereupon, the Pontiff gave his approbation to the new institute, and would have it called the Order of the Most Holy Trinity for the Ransom of captives, bidding its members wear a white habit, with a red and blue cross.

The Order being thus established, its holy Founders returned to France, and erected their first Monastery at Cerfroid, in the diocese of Meaux. Felix was left to govern it, and John returned, accompanied by a few of his brethren, to Rome. Innocent the Third gave them the house, church, and hospital of Saint Thomas de Formis, together with various revenues and possessions. He also gave them letters to Miramolin, king of Morocco, and thus was prosperously begun the work of Ransom. John afterwards went into Spain, a great portion of which country was then under the Saracen yoke. He stirred up kings, princes, and others of the Faithful, to compassion for the captives and the poor. He built monasteries, founded hospitals, and saved the souls of many captives by purchasing their freedom. Having, at length, returned to Rome, he spent his days in doing good. Worn out by incessant labour and sickness, and burning with a most ardent love of God and his neighbour, it was evident that his death was at hand. Wherefore, calling his brethren round him, he eloquently besought them to labour in the work of Ransom, which heaven had intrusted to them, and then slept in the Lord, on the sixteenth of the Calends of January (December 17th), in the year of grace 1213. His body was buried with the honour that was due to him in the same Church of Saint Thomas de Formis.

Life of St. John of Matha

A.D. 1213

St. John was born of very pious and noble parents, at Faucon, on the borders of Provence, June the 24th, 1169, and was baptized John, in honor of St. John the Baptist. His mother dedicated him to God by a vow from his infancy. His father, Euphemius, sent him to Aix, where he learned grammar, fencing, riding, and other exercises fit for a young nobleman. But his chief attention was to advance in virtue. He gave the poor a considerable part of the money his parents sent him for his own use: he visited the hospital every Friday, assisting the poor sick, dressing and cleansing their sores, and affording them all the comfort in his power.

Being returned home, he begged his father's leave to continue the pious exercises he had begun, and retired to a little hermitage not far from Faucon, with the view of living at a distance from the world, and united to God alone by mortification and prayer. But finding his solitude interrupted by the frequent visits of his friends, he desired his father's consent to go to Paris to study divinity, which he easily obtained. He went through these more sublime studies with extraordinary success, and proceeded doctor of divinity with uncommon applause, though his modesty gave him a reluctancy to that honor. He was soon after ordained priest, and said his first mass in the bishop of Paris's chapel, at which the bishop himself, Maurice de Sully, the abbots of St. Victor and of St. Genevieve, and the rector of the university, assisted; admiring the graces of heaven in him, which appeared in his extraordinary devotion on this occasion, as well as at his ordination.

On the day he said his first mass, by a particular inspiration from God, he came to a resolution of devoting himself to the occupation of ransoming Christian slaves from the captivity they groaned under among the infidels: considering it as one of the highest acts of charity with respect both to their souls and bodies. But before he entered upon so important a work, he thought it needful to spend some time in retirement, prayer, and mortification. And having heard of a holy hermit, St. Felix Valois, living in a great wood near Gandelu, in the diocese of Meux, he repaired to him and begged he would admit him into his solitude, and instruct him in the practice of perfection. Felix soon discovered him to be no novice, and would not treat him as a disciple, but as a companion. It is incredible what progress these two holy solitaries made in the paths of virtue, by perpetual prayer, contemplation, fasting, and watching.

One day, sitting together on the bank of a spring, John disclosed to Felix the design he had conceived on the day on which he said his first mass, to succor the Christians under the Mahometan slavery, and spoke so movingly upon the subject that Felix was convinced that the design was from God, and offered him his joint concurrence to carry it into execution. They took some time to recommend it to God by prayer and fasting, and then set out for Rome in the midst of a severe winter, towards the end of the year 1197, to obtain the pope's benediction. They found Innocent III promoted to the chair of St. Peter, who being already informed of their sanctity and charitable design by letters of recommendation from the bishop of Paris, his holiness received them as two angels from heaven; lodged them in his own palace, and gave them many long private audiences. After which he assembled the cardinals and some bishops in the palace of St. John Lateran, and asked their advice. After their deliberations he ordered a fast and particular prayers to know the will of heaven. At length, being convinced that these two holy men were led by the spirit of God, and that great advantages would accrue to the church from such an institute, he consented to their erecting a new religious order, and declared St. John the first general minister. The bishop of Paris, and the abbot of St. Victor, were ordered to draw up their rules, which the pope approved by a bull, in 1198. He ordered the religious to wear a white habit, with a red and blue cross on the breast, and to take the name of the order of the Holy Trinity. He confirmed it some time after, adding new privileges by a second bull, dated in 1209.

The two founders having obtained the pope's blessing and certain indults or privileges, returned to France, and presented themselves to the king, Philip Augustus, who authorized the establishment of their Order in his kingdom, and favored it with his liberalities. Gaucher III, lord of Chatillon, gave them land whereon to build a convent. Their number increasing, the same lord, seconded by the king, gave them Cerfroid, the place in which St. John and St. Felix concerted the first plan of their institute. It is situated in Brie, on the confines of Valois. This house of Cerfroid, or De Cervo frigido, [was] the chief of the order. The two saints founded many other convents in France, and sent several of their religious to accompany the counts of Flanders and Blois, and other lords, to the holy war. Pope Innocent III wrote to recommend these religious to Miramolin, king of Morocco; and St. John sent thither two of his religious in 1201, who redeemed one hundred and eighty-six Christian slaves the first voyage. The year following, St. John went himself to Tunis, where he purchased the liberty of one hundred and ten more. He returned into Provence, and there received great charities, which he carried into Spain, and redeemed many in captivity under the Moors. On his return he collected large alms among the Christians towards this charitable undertaking. His example produced a second order of Mercy, instituted by St. Peter Nolasco, in 1235.

St. John made a second voyage to Tunis in 1210, in which he suffered much from the infidels, enraged at his zeal and success in exhorting the poor slaves to patience and constancy in their faith. As he was returning with one hundred and twenty slaves he had ransomed, the barbarians took away the helm from his vessel, and tore all its sails, that they might perish in the sea. The saint, full of confidence in God, begged him to be their pilot, and hung up his companions’ cloaks for sails, and, with a crucifix in his hands, kneeling on the deck, singing psalms, after a prosperous voyage, they all landed safe at Ostia, in Italy. Felix, by this time, had greatly propagated his order in France, and obtained for it a convent in Paris, in a place where stood before a chapel of St. Mathurin, whence these religious in France are called Mathurins.

St. John lived two years more in Rome, which he employed in exhorting all to penance with great energy and fruit. He died… aged sixty-one. He was buried in his church of St. Thomas, where his monument yet remains, though his body has been translated into Spain. Pope Honorius III confirmed the rule of this order a second time. By the first rule, they were not permitted to buy any thing for their sustenance except bread, pulse, herbs, oil, eggs, milk, cheese, and fruit; never flesh nor fish: however, they might eat flesh on the principal festivals, on condition it was given them. They were not, in travelling, to ride on any beasts but asses.

St. Chrysostom elegantly and pathetically extols the charity of the widow of Sarepta, whom neither poverty nor children, nor hunger, nor fear of death, withheld from affording relief to the prophet Elias, and he exhorts every one to meditate on her words, and keep her example present to his mind. “How hard or insensible soever we are,” says he, “they will make a deep impression upon us, and we shall not be able to refuse relief to the poor, when we have before our eyes the generous charity of this widow. It is true, you will tell me, that if you meet with a prophet in want, you could not refuse doing him all the good offices in your power. But what ought you not to do for Jesus Christ, who is the master of the prophets? He takes whatsoever you do to the poor as done to himself.” When we consider the zeal and joy with which the saints sacrificed themselves for their neighbors, how must we blush at, and condemn our insensibility at the spiritual and the corporal calamities of others! The saints regarded affronts, labors, and pains, as nothing for the service of others in Christ: we cannot bear the least word or roughness of temper.

Dear friend and Liberator of slaves! pray, during this holy Season, for those who groan under the captivity of sin and Satan, for those, especially, who, taken with the phrensy of earthly pleasures, feel not the weight of their chains, but sleep on peacefully through their slavery. Ransom them by thy prayers, convert them to the Lord their God, lead them back to the land of freedom. Pray for France which was thy country, and save her from infidelity.

Taken from: The Liturgical Year – Septuagesima, Edition 1870;

The Lives of the Fathers,

Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, Vol. I, 1903; and

The Divine Office for the use of the Laity, Volume I, 1806.

St. John of Matha, pray for us.