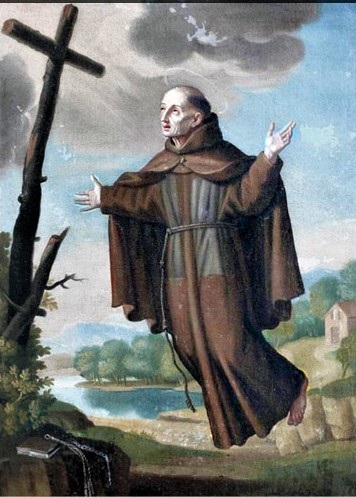

October 19, 2017: ST. PETER OF ALCANTARA

October 19, 2017: ST. PETER OF ALCANTARA, CONFESSOR

Rank: Double.

‘O happy penance, which hath obtained me so great a reward!’

Prayer (Collect).

O God, who wast pleased to render blessed Peter thy Confessor, eminent for his exemplary penance and wonderful contemplation; grant us, we beseech thee; that, being duly mortified in our bodies, our souls may be fitly disposed for the receiving thy heavenly graces. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, thy Son, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God, world without end. Amen.

‘O HAPPY penance, which has won me such glory!’ said the saint of to-day at the threshold of heaven. And on earth, Teresa of Jesus (of Avila) wrote of him: ‘Oh! what a perfect imitator of Jesus Christ God has just taken from us, by calling to his glory that blessed religious, Brother Peter of Alcantara! The world, they say, is no longer capable of such high perfection; constitutions are weaker, and we are not now in the olden times. Here is a saint of the present day; yet his manly fervour equalled that of past ages; and he had a supreme disdain for everything earthly. But without going barefoot like him, or doing such sharp penance, there are very many ways in which we can practise contempt of the world, and which our Lord will teach us as soon as we have courage. What great courage must the holy man I speak of have received from God, to keep up for forty-seven years the rigorous penance that all now know!

Of all his mortifications, that which cost him most at the beginning was the overcoming of sleep; to effect this he would remain continually on his knees, or else standing. The little repose he granted to nature he took sitting, with his head leaning against a piece of wood fixed to the wall; indeed, had he wished to lie down, he could not have done so, for his cell was only four feet and a half in length. During the course of all these years, he never put his hood up, however burning the sun might be, or however heavy the rain. He never used shoes or stockings. He wore no other clothing than a single garment of rough, coarse cloth; I found out, however, that for twenty years he wore a hair-shirt made on plates of tin, which he never took off. His habit was as narrow as it could possibly be; and over it he put a short cloak of the same material; this he took off when it was very cold, and left the door and small window of his cell open for a while; then he shut them and put his cape on again, which he said was his manner of warming himself and giving his body a little better temperature. He usually ate but once in three days; and when I showed some surprise at this, he said it was quite easy when one was accustomed to it. His poverty was extreme; and such was his mortification, that, as he acknowledged to me, he had, when young, spent three years in a house of his Order without knowing any one of the religious except by the sound of his voice; for he had never lifted up his eyes; so that, when called by the rule to any part of the house, he could find his way only by following the other brethren. He observed the same custody of the eyes when on the roads. When I made his acquaintance, his body was so emaciated that it seem to be formed of the roots of trees.’ (St. Teresa. Life, xxvii. xxx.)

To this portrait of the Franciscan reformer [St. Peter of Alcantara] drawn by the reformer of Carmel [St. Teresa of Avila], the Church will add the history of his life. Three illustrious and worthy families… form the first Order of St. Francis, known as the Conventuals, the Observantines, and the Capuchins. A pious emulation for more and more strict reform, brought about in the Observance itself, a subdivision into the Observantines proper, the Reformed, the Discalced or Alcantarines, and the Recollets. This division, which was historical rather than constitutional, no longer exists; for, on the feast of the patriarch of Assisi, October 4, 1897, the sovereign Pontiff Leo XIII thought fit to reunite the great family of the Observance, which is hence forth known as the Order of Friars Minor.

[Let us read the Church’s account on St. Peter of Alcantara.]

Peter was born of noble parents at Alcantara in Spain, and from his earliest years gave promise of his future sanctity. At the age of sixteen, he entered the Order of Friars Minor, in which he became an example of every virtue. He undertook by obedience the office of preaching, and led numberless sinners to sincere repentance. Desirous of bringing back the Franciscan Order to its original strictness, he founded, by God’s assistance and with the approbation of the apostolic See, a very poor little convent at Pedroso. The austere manner of life, which he was there the first to lead, was afterwards spread in a wonderful manner throughout Spain and even into the Indies. He assisted St. Teresa, whose spirit he approved, in carrying out the reform of Carmel. And she having learned from God that whoever asked anything in Peter’s name would be immediately heard, was wont to recommend herself to his prayers, and to call him a saint, while he was still living.

Peter was consulted as an oracle by princes; but he avoided their honours with great humility, and refused to become confessor to the emperor Charles V. He was a most rigid observer of poverty, having but one tunic, and that the meanest possible. Such was his delicacy with regard to purity, that he would not allow the brother, who waited on him in his last illness, even lightly to touch him. By perpetual watching, fasting, disciplines, cold, and nakedness, and every kind of austerity, he brought his body into subjection; having made a compact with it, never to give it any rest in this world. The love of God and of his neighbour was shed abroad in his heart, and at times burned so ardently that he was obliged to escape from his narrow cell into the open, that the cold air might temper the heat that consumed him.

Admirable was his gift of contemplation. Sometimes, while his spirit was nourished in this heavenly manner, he would pass several days without food or drink. He was often raised in the air, and seen shining with wonderful brilliancy. He passed dry-shod over the most rapid rivers. When his brethren were absolutely destitute, he obtained for them food from heaven. He fixed his staff in the earth, and it suddenly became a flourishing fig-tree. One night when he was journeying in a heavy snow-storm, he entered a ruined house; but the snow, lest he should be suffocated by its dense flakes, hung in the air and formed a roof above him. He was endowed with the gifts of prophecy and discernment of spirits as St. Teresa testifies. At length, in his sixty-third year, he passed to our Lord at the hour he had foretold, fortified by a wonderful vision and the presence of the saints. St. Teresa, who was at a great distance, saw him at that same moment carried to heaven. He afterwards appeared to her, saying: O happy penance, which has won me such great glory! He was rendered famous after death by many miracles, and was enrolled among the saints by (Pope) Clement IX.

Life of St. Peter of Alcantara.

Christ declares the spirit and constant practice of penance to be the foundation of a Christian or spiritual life. This great and most important maxim, which in these latter ages is little understood, even amongst the generality of those who call themselves Christians, is set forth by the example of this saint to confound our sloth, and silence all our vain excuses. St. Peter was born at Alcantara, a small town in the province of Estramadura, in Spain, in 1499. His father, Alphonso Garavito, was a lawyer, and governor of that town; his mother was of good extraction, and both were persons eminent for their piety and personal merit in the world. Upon the first dawn of reason Peter discovered the most happy dispositions to virtue, and seemed a miracle of his age in fervour and unwearied constancy in the great duty of prayer from his childhood, and his very infancy. He had not finished his philosophy in his own country, when his father died. Some time after this loss he was sent to Salamanca to study the canon law. During the two years that he spent in that university, he divided his whole time between the church, the hospital, the school, and his closet. In 1513 he was recalled to Alcantara, where he deliberated with himself about the choice of a state of life. On one side the devil represented to him the fortune and career which were open to him in the world; on the other side, listening to the suggestions of divine grace, he considered the dangers of such a course, and the happiness and spiritual advantages of holy retirement. These sunk deep into his heart, and he felt in his soul a strong call to a religious state of life, in which he should have no other concern but that of securing his own salvation. Resolving, therefore, to embrace the holy Order of St. Francis, in the sixteenth year of his age he took the habit of that austere rule in the solitary convent of Manjarez, situated in the mountains which ran between Castile and Portugal. An ardent spirit of penance determined his choice of this rigorous institute in imitation of the Baptist, and he was so much the more solicitous after his engagement to cultivate and improve the same with particular care, as he was sensible that the characteristical virtues of each state ought to form the peculiar spirit of their sanctity who serve God in it.

During his novitiate he laboured to subdue his domestic enemy by the greatest humiliations, most rigorous fasts, incredible watchings, and other severities. Such was his fervour that the most painful austerities had nothing frightful or difficult for him; his disengagement from the world, from, the very moment he renounced it, was so entire that he seemed in his heart to be not only dead or insensible, but even crucified to it, and to find all that a pain which flatters the senses and the vanity of men in it; and the union of his soul with his Creator seemed to suffer no interruption from any external employments. He had first the care of the vestry (which employment was most agreeable to his devotion), then of the gate, and afterwards of the cellar; all which offices he discharged with uncommon exactness, and without prejudice to his recollection. That his eyes and other senses might be more easily kept under the government of reason, and that they might not, by superfluous curiosity, break in upon the interior recollection of his mind, such was the restraint he put upon them that he had been a considerable time a religious man without ever knowing that the church of his convent was vaulted. After having had the care of serving the refectory for half a year, he was chid by the superior for having never given the friars any of the fruit in his custody; to which the servant of God humbly answered, he had never seen any. The truth was he had never lifted up his eyes to the ceiling, where the fruit was hanging upon twigs, as is usual in countries where grapes are dried and preserved. He lived four years in a convent without taking notice of a tree that grew near the door. He ate constantly for three years in the same refectory without seeing any other part of it than a part of the table where he sat, and the ground on which he trod. He told St. Teresa that he once lived in a house three years without knowing any of his religious brethren but by their voices. From the time that he put on the religious habit to his death he never looked any woman in the face. These were the marks of a true religious man, who studied perfectly to die to himself. His food was for many years only bread moistened in water, or unsavoury herbs, of which, when he lived a hermit, he boiled a considerable quantity together that he might spend the less time in serving his body, and ate them cold, taking a little at once for his refection, which for a considerable time he made only once in three days. Besides these unsavoury herbs he sometimes allowed himself a porridge made with salt and vinegar; but this only on great feasts. For some time his ordinary mess was a soup made of beans; his drink was a small quantity of water. He seemed, by long habits of mortification, to have almost lost the sense of taste in what he ate; for when a little vinegar and salt was thrown into a porringer of warm water he took it for his usual soup of beans. He had no other bed than a rough skin laid on the floor, on which he knelt great part of the night, leaning sometimes on his heels for a little rest; but he slept sitting, leaning his head against a wall. His watchings were the most difficult and the most incredible of all the austerities which he practised; to which he inured himself gradually, that they might not be prejudicial to his health; and which, being of a robust constitution of body, he found himself able to bear. He was assailed by violent temptations, and cruel spiritual enemies; but, by the succour of divine grace, and the arms of humility and prayer, was always victorious.

A few months after his profession, Peter was sent from Manjarez to a remote retired convent near Belviso; where he built himself a cell with mud and the branches of trees, at some distance from the rest, in which he practised extra-ordinary mortifications without being seen. About three years after, he was sent by his provincial to Badajos, the metropolis of Estramadura, to be superior of a small friary lately established there, though he was at that time but twenty years old. The three years of his guardianship, or wardenship, appeared to him a grievous slavery. When they were elapsed he received his provincial's command to prepare himself for holy orders. Though he earnestly begged for a longer delay, he was obliged to acquiesce, and was promoted to the priesthood in 1524, and soon after employed in preaching. The ensuing year he was made guardian of Placentia. In all stations of superiority he considered himself as a servant to his whole community, and looked upon his post only as a strict obligation of encouraging the rest in the practice of penance by his own example.

The love of retirement being always St. Peter's predominant inclination, he made it his earnest petition to his superiors that he might be placed in some remote solitary convent, where he might give himself up to the sweet commerce of divine contemplation. In compliance with his request he was sent to the convent of St. Onuphrius, at Lapa, near Soriana, situated in a frightful solitude; but, at the same time, he was commanded to take upon him the charge of guardian, or warden, of that house. In that retirement he composed his golden book on Mental Prayer, at the request of a pious gentle man who had often heard him speak on that subject. This excellent little treatise was justly esteemed a finished master piece on this important subject, by St. Teresa, Lewis of Granada, St. Francis of Sales, Pope Gregory XV, Queen Christina of Sweden, and others. In it the great advantages and necessity of mental prayer are briefly set forth; all its parts and its method are explained, and exemplified in affections of divine love, praise, and thanksgiving, and especially of supplication or petition. Short meditations on the last things, and on the passion of Christ, are added as models. Upon the plan of this book Lewis of Granada, and many others, have endeavoured to render the use of mental prayer easy and familiar among Christians, in an age which owes all its spiritual evils to a supine neglect of this necessary means of interior true virtue. Our saint has left us another short treatise, On the Peace of the Soul, or On an Interior Life, no less excellent than the former. St. Peter was himself an excellent proficient in the school of divine love, and in the exercises of heavenly contemplation. His prayer and his union with God was habitual. He said mass with a devotion that astonished others, and often with torrents of tears, or with raptures. He was seen to remain in prayer a whole hour, with his arms stretched out, and his eyes lifted up without moving. His ecstasies in prayer were frequent, and sometimes of long continuance. So great was his devotion to the mystery of the incarnation, and the holy sacrament of the altar, that the very mention or thought of them frequently sufficed to throw him in a rapture. The excess of heavenly sweetness, and the great revelations which he received in the frequent extraordinary unions of his soul with God are not to be expressed. In the jubilation of his soul, through the impetuosity of the divine love, he sometimes was not able to contain himself from singing the divine praises aloud in a wonderful manner. To do this more freely he sometimes went into the woods, where the peasants who heard him sing took him for one who was beside himself.

The reputation of St. Peter having reached the ears of John III, King of Portugal, that prince was desirous to consult him upon certain difficulties of conscience, and St. Peter received an order from his provincial to repair to him at Lisbon. He did not make use of the carriages which the king had ordered to be ready for him, but made the journey barefoot, without sandals, according to his custom. King John was so well satisfied with his answers and advice, and so much edified by his saintly comportment, that he engaged him to return again soon after. But though they had fitted up apartments like a cell, with an oratory for him, and allowed him liberty to give himself up wholly to divine contemplation, according to his desire, yet he found the conveniences too great, and the palace not agreeable to his purposes. A great division having happened among the townsmen of Alcantara, he took this opportunity to leave the court, in order to reconcile those that were at variance. His presence and pathetic discourses easily restored peace among the inhabitants of Alcantara. This affair was scarcely finished when, in 1538, he was chosen provincial of the province of St. Gabriel, or of Estramadura, which, though it was of the conventuals, had adopted some time before certain constitutions of a reform. The age required for this office being forty years, the saint warmly urged that he was only thirty-nine; but all were persuaded that his prudence and virtue were an overbalance. Whilst he discharged this office he drew up several severe rules of reformation, which he prevailed on the whole province to accept in a chapter which he held at Placentia for this purpose, in 1540.

In 1544, our saint was recalled by his own superiors into Spain, and received by his brethren in the province of Estramadura with the greatest joy that can be expressed. Heavenly contemplation being always his favourite inclination, though, by obedience, he often employed himself in the service of several churches, and in the direction of devout persons, he procured his superior's leave to reside in the most solitary convents, chiefly at St. Onuphrius's, near Soriano. After four years spent in this manner, he was allowed, at the request of Prince Lewis, the king's most pious brother, and of the Duke of Aveiro, to return to Portugal. During three years that he stayed in that kingdom, he raised his congregation of Arâbida to the most flourishing condition, and, in 1550, founded a new convent, near Lisbon. This custody was erected into a province of the Order, in 1560. His reputation for sanctity drew so many eyes on him, and gave so much interruption to his retirement, that he hastened back to Spain, hoping there to hide himself in some solitude. Upon his arrival at Placentia, in 1551, his brethren earnestly desired to choose him provincial; but the saint turned himself into every shape to obtain the liberty of living some time to himself, and at length prevailed. In 1553 he was appointed custos by a general chapter held at Salamanca. In 1554 he formed a design of establishing a reformed congregation of friars upon a stricter plan than before; for which he procured himself to be empowered by a brief obtained of Pope Julius III. His project was approved by the provincial of Estramadura, and by the Bishop of Coria, in whose diocess the saint, with one fervent companion, made an essay of this manner of living in a small hermitage. A short time after, he went to Rome, and obtained a second brief, by which he was authorized to build a convent according to this plan. At his return a friend founded a convent for him, such a one as he desired, near Pedroso, in the diocess of Palentia, in 1555, which is the date of this reformed institute of Franciscans, called The Barefooted, or of the strictest observance of St. Peter of Alcantara. This convent was but thirty-two feet long and twenty-eight wide; the cells were exceeding small, and one-half of each was filled with a bed consisting of three boards: the saint's cell was the smallest and most inconvenient. The church was comprised in the dimensions given above, and of a piece with the rest. It was impossible for persons to forget their engagement in a penitential life, whilst their habitations seemed rather to resemble graves than chambers. The Count of Oropeza founded upon his estates two other convents for the saint; and certain other houses received his reformation, and others were built by him. In 1561, he formed them into a province, and drew up certain statutes, in which he orders that each cell should only be seven feet long, the infirmary thirteen, and the church twentyfour; the whole circumference of a convent forty or fifty feet; that the number of friars in a convent should never exceed eight; that they should always go bare-foot, without socks or sandals; should lie on the boards, or mats laid on the floor; or, if the place was low and damp, on beds raised one foot from the ground; that none, except in sickness, should ever eat any flesh, fish, or eggs, or drink wine; that they should employ three hours everyday in mental prayer, and should never receive any retribution for saying mass. The general appointed St. Peter commissary of his Order in Spain in 1556, and he was confirmed in that office by Pope Paul IV, in 1559. In 1561, whilst he was commissary, he was chosen provincial of his reformed Order, and, going to Rome, begged a confirmation of this institute. Pius IV, who then sat in St. Peter's chair, by a bull, dated in February, 1562, exempted this congregation from all jurisdiction of the conventual Franciscans (under whom St Peter had lived), and subjected it to the minister-general of the Observantins, with this clause, that it is to be maintained in the perpetual observance of the rules and statutes prescribed by St. Peter. It is propagated into several provinces in Spain, and is spread into Italy, each province in this reform consisting of about ten religious houses.

When the Emperor Charles V, after resigning his dominions, retired to the monastery of St. Justus, in Estramadura, of the Order of Hieronymites, in 1555, he made choice of St. Peter for his confessor, to assist him in his preparation for death; but the saint, foreseeing that such a situation would be incompatible with the exercises of assiduous contemplation and penance to which he had devoted himself, declined that post with so much earnestness, that the emperor was at length obliged to admit his excuses. The saint, whilst in quality of commissary he made the visitation of several monasteries of his Order, arrived at Avila in 1559. St. Teresa laboured at that time under the most severe persecutions from her friends, and her very confessors, and under interior trials from scruples and anxiety, fearing at certain intervals, as many told her, that she might be deluded by an evil spirit. A certain pious widow lady, named Guiomera d'Ulloa, an intimate friend of St. Teresa, and privy to her troubles and afflictions, got leave of the provincial of the Carmelites that she might pass eight days in her house, and contrived that this great servant of God should there treat with her at leisure. St. Peter, from his own experience and knowledge in heavenly communications and raptures, easily understood her, cleared all her perplexities, gave her the strongest assurances that her visions and prayer were from God, loudly confuted her calumniators, and spoke to her confessor in her favour. He afterwards exceedingly encouraged her in establishing her reformation of the Carmelite Order, and especially in founding it in the strictest poverty. Out of his great affection and compassion for her under her sufferings, he told her in confidence many things concerning the rigorous course of penance in which he had lived for seven-and-forty years. “He told me,” says she, “that, to the best of my remembrance, he had slept but one hour and a half in twenty-four hours for forty years together; and that, in the beginning, it was the greatest and most troublesome mortification of all to overcome himself in point of sleep; and that in order for this, he was obliged to be always either kneeling or standing on his feet: only when he slept he sat with his head leaning aside upon a little piece of wood fastened for that purpose in the wall. As to the extending his body at length in his cell, it was impossible for him, his cell not being above four feet and a half in length. In all these years he never put on his capouch or hood, how hot soever the sun, or how violent soever the rain might be; nor did he ever wear any thing upon his feet, nor any other garment than his habit of thick coarse sackcloth (without any other thing next his skin), and this short and scanty, and as straight as possible, with a short mantle or cloak of the same over it. He told me, that when the weather was extreme cold, he was wont to put off his mantle, and to leave the door and the little window of his cell open, that when he put his mantle on again and shut his door, his body might be somewhat refreshed with this additional warmth. It was usual with him to eat but once in three days; and he asked me why I wondered at it, for it was very possible to one who had accustomed himself to it. One of his companions told me that sometimes he ate nothing at all for eight days; but that, perhaps, might be when he was in prayer; for he used to have great raptures, and vehement transports of divine love, of which I was once an eye-witness. His poverty was extreme, and so also was his mortification, even from his youth. He told me he had lived three years in a house of his Order without knowing any of the friars but by their speech; for he never lifted up his eyes; so that he did not know which way to go to many places which he often frequented, if he did not follow the other friars. This likewise happened to him in the roads. When I came to know him he was very old, and his body so extenuated and weak, that it seemed not to be composed, but as it were of the roots of trees, and was so parched up that his skin resembled more the dried bark of a tree than flesh. He was very affable, but spoke little, unless some questions were asked him; and he answered in few words, but in these he was agreeable, for he had an excellent understanding.” St. Teresa observes, that though a person cannot perform such severe penance as this servant of God did, yet there are many other ways whereby we may tread the world under our feet; and our Lord will teach us these ways when he finds a mind that is fit. To deny the obligation and necessity of some degree of exterior penance and mortification (which some now-a-days seem almost to cashier in practice) would be an error in faith. The extraordinary severities which the Baptist and so many other saints exercised upon themselves, ought to be to us sinners a subject of humiliation and self-reproach. We ought not to lose courage if we do not, or cannot, watch and fast as they did; but then we ought at least to be the more diligent in bearing labours, pains, humiliations, and sickness with patience, and in the practice of interior self-denials, humility, and meekness.

St. Peter was making the visitation of his convents, and confirming his religious in that perfect spirit of penance with which he had inspired them, when he fell sick in the convent of Viciosa. The Count of Oropeza, upon whose estate that house was situated, caused him against his will to be removed to his own house, and to take medicines, and good nourishing food; but these instead of relieving aggravated his distemper, his pain in his stomach grew more violent, his fever redoubled, and an ulcer was formed in one of his legs.

The holy man, perceiving that his last hour approached, would be carried to the convent of Arenas, that he might die in the arms of his brethren. He was no sooner arrived there but he received the holy sacraments. In his last moments he exhorted his brethren to perseverance, and to the constant love of holy poverty. Seeing he was come to the end of his course, he repeated those words of the Psalmist, “I have rejoiced in those things which have been said to me. We shall go into the house of the Lord.” Having said these words, he rose upon his knees, and stooping in that posture calmly expired on the 18th of October, in the year 1562, of his age sixty-three. St. Teresa, after mentioning his happy death, says, “Since his departure our Lord has been pleased to let me enjoy more of him than I did when he was alive; he has given me advice and counsel in many things and I have frequently seen him in very great glory. The first time that he appeared to me, he said, ‘O happy penance, which hath obtained me so great a reward!’ with many other things. A year before he died, he appeared to me when we were at a distance from one another, and I understood that he was to die, and I advertised him of it. When he gave up the ghost he appeared to me, and told me that he was going to rest. Behold here the severe penance of his life ending in so much glory, that methinks he comforts me now much more than when he was here. Our Lord told me once that men should ask nothing in his name wherein he would not hear them. I have recommended many things to him, that he might beg them of our Lord, and I have always found them granted.” St. Peter was beatified by Gregory XV in 1622, and canonized by Clement IX in 1669.

We admire in the saints the riches and happiness of which they were possessed in the inestimable treasure of the divine love. They attained to, and continually improved this grace in their souls by the exercise of heavenly contemplation, and a perfect spirit of prayer; and laid the foundation of this spiritual tower by a sincere spirit of humility and penance. It costs nothing for a man to say that he desires to love God; but he lies to his own soul unless he strive to die to himself. The senses must be restrained and taught to obey, and the heart purged from sensual and inordinate attachments before it can be moulded anew, rendered spiritual, and inflamed with the chaste affections of pure and perfect love. This is the great work of divine grace in weak impure creatures; but the conditions are, that perfect humility and penance prepare the way, and be the constant attendants of this love. How imperfect is it in our souls, if it is there at all! and how much is it debased by a mixture of sensual affections, and the poisonous stench of self-love not sufficiently vanquished and extinguished, because we neglect these means of grace! A sensual man cannot conceive those things which belong to God.

Taken from: The Liturgical Year - Time after Pentecost, Vol. V, Edition 1910;

The Lives of the

Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints, Vol. II; and

The Divine Office for the use of the Laity, Volume II, 1806.

St. Peter of Alcantara, pray for us.